Silver Wordsmith: An author's journey |

|

I’ve found it difficult to find the right words to say.

I find silence just as hard to maintain. I have made no secret about my opinion of the country I grew up in – the one my parents and grandparents were born. I consider it a fortuitous badge of honour that my family moved away three weeks before the man currently running Russia came to power. And I want to be clear, when I use the word ‘running’, I mean that he is running it into the ground. There are few, if any, pairs of countries on this planet that are as interconnected through family as Russia and Ukraine are. This war of aggression is nothing short of fratricide, perpetuated by a man intent on carving his legacy using the blood of his people and the blood of the people closest to them. No matter what bald-faced lies are fed about the alleged noble intentions of a war that is laughably passed off as a war of liberation, this is nothing short of a crime against humanity. There will be be forever etched into the history books something called the Russo-Ukrainian War – an abomination that should have never come to be. And I know that people around the world are horrified by the newest invasion but they won’t be truly able to appreciate the heaviness of this tragedy. To me, the conflict would forever be defined by a question that would haunt me forever – the first words my mom said to me when we first spoke after the invasion had been declared: “How does it feel waking up an aggressor?” How does it feel to wake up and once again be a part of a great people led to commit great harm by a seemingly ceaseless succession of evil men? How does it feel to look in the mirror and see yourselves related to the bad guys? There are no words that I can say that would properly convey how much I condemn this war, how much I condemn what we’re doing, because, make no mistake, it is still that ‘we’ that sits like a thorn in my heart. There is a naïve hopeful part of me that believes this can kick off a chain of events that can turn the page to a new chapter in Russian history, and perhaps we will finally wake up and have something to be proud of.

0 Comments

I’ve noticed a curious trend in my writing recently to do with the setting of my stories. First question of course is how does one “notice” their own trend, aren’t I the one setting them? To that I answer that you’d be surprised what you don’t notice about your writing until you’ve had a chance to step back and take a look. Specifically, in my case I’ve been setting more of my stories in Russia, and with a particular slant to them as well.

Thinking back on my high school churn of short stories, I can’t recall any of them being explicitly set in Russia except one – the mostly autobiographical story of a kid with a heart condition trying to play hockey (don’t worry folks, knock on wood but this seems to have resolved itself – the heart condition, not the hockey, which is an affliction that refuses to leave me). There was another one that was loosely based on the events of one of the bombings of the Russian parliament in the early post-Soviet Union days, but it was set in an otherwise nameless fictional European country. An odd pattern give how much of writing advice is “write what you know”. This seems to have begun to shift in the past few years. Firstly, my second novel that I’m currently 70K words into is set predominantly in Russia. You can read more about it here but the gist is that someone who immigrates from Russia as a kid wakes up in his mid-twenties back in Moscow living the life he would have supposedly led if he had never left. Some parts are set in Canada, but otherwise it’s a Russian-set novel through and through. Secondly, my third long-form writing project, which recently surpassed 15K but is still in the experimental stage is an autobiographical (or possible semi-autobiographical, since I’m still toying with this) accounting of my relationship with my father set against my immigrant experience. Most of this takes place in Canada but since I immigrated after I’d turned thirteen Russia plays a prominent role here as well. And finally are my short stories. My production of these has slowed down considerably and I think on average I’ve completed about two a year for the last few years. Still, two out of the last four that I’ve worked on are set exclusively in Russia, with a curious common theme between them. The one that I completed last year, “Grisha and Kolya”, follows two kids, one who has a developmental delay and the other who bullies him regardless, not for his disability, but his perceived class privilege. The other, "Snowdrops", is about an older woman living by herself just above the concrete overhang of a Soviet-era apartment block and her struggles with a juvenile delinquent who keeps throwing things out of their apartment to smash right outside her window. Both of these stories are pure fiction, but draw heavily on my own experience in Russia, including elements of myself lurking in the background, as I use the stories to try to deal with some of of the mistakes from my childhood. It’s a shift to be sure, and not entirely a mysterious one. High school wasn’t exactly an encouraging environment for me to explore my Russianness, as I found mostly what my identity earned me was a heavy dose of bullying. This time in my life I was trying to figure just how “Canadian” I could be given my background, and learning how heavy the first part of the hyphenation of “Russian-Canadian” would be. Over the years, like Canadian society has finally begun to do, I’ve started moving past the “hyphenated” identity, allowing both to exist independently in the amounts that are true to myself and not some externally-dictated vision of what I should be. I think for this reason I’ve felt more comfortable drawing on my Russian influence directly, since each foray no longer threatens to envelop me in an identity crisis in the same way. I’m excited as to where this new direction in my writing will lead me. My favourite author, Kazuo Ishiguro, set his first two novels in Japan, even though he emigrated from that country at the age of five. Not to say that I’m anywhere close to expecting the same kind of success, but it’s a great source of inspiration, and who’s to say what will happen next.  One Pushkin's other great cultural contributions was wicked sideburns One Pushkin's other great cultural contributions was wicked sideburns

Recently I was doing some preliminary research for a future project that’s currently in the “dream” phase, that is, it’s not a full-fledged project that will currently take up time (as I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, I just added a new work to my plate and even I’m not so deranged as to spread myself even thinner). This particular line of research led me to 19th century Russian literature where I discovered a curious but quintessentially Russian pattern – in order to be a great Russian writer in the 19th century, all one had to do was die.

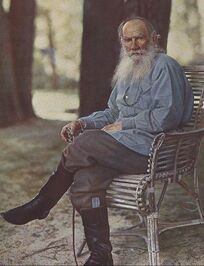

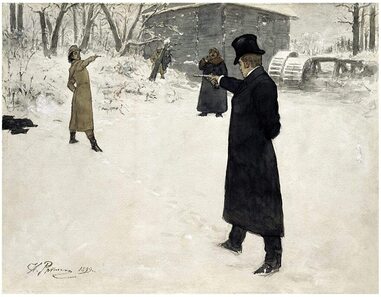

Some of these names won’t be familiar to you. Western readers tend to focus on those that were prolific towards the end of that century, like Tolstoy, Dostoevsky and Chekhov, but some of these names are bigger in Russia than even the three I mentioned. Alexander Pushkin, for example, is considered by most to be the greatest Russian poet and the founder of modern Russian literature. He’s a household name with a multitude of statues honouring him. Yet, he had died at the ripe age of 37 in 1837, shot in the stomach during a duel (the 29th of Pushkin’s career) by a man allegedly trying to seduce Pushkin’s wife. Mikhail Lermontov, the greatest figure in Russian Romanticism who carried the mantle of Russia’s greatest poet after Pushkin’s death did so for only four years, dying at the age of 26, also in a duel. Apparently, he had teased one of his military cadet school friends so mercilessly over his attire that the man, despite likely having the knowledge that Lermontov planned to throw away his shot, still shot the poet through the heart.  When you've lived longer than the two greatest Russian poets combined When you've lived longer than the two greatest Russian poets combined

No less tragically but far less colourfully, the previously mentioned Chekov died of tuberculosis at age 44. And Nikolai Gogol, the author of Dead Souls, one of my all-time favourite novels, passed after refusing food for nine straight days amidst a struggle with mental health issues and a crisis of spirituality. He was 42.

The worst fate of the lot befell Alexander Griboyedov, one of Pushkin’s mentors and Russia’s appointed ambassador to Iran. After Griboyedov provided sanctuary to several Armenian slaves who had escaped a harem, a frenzied mob broke into the embassy and murdered the Russian ambassador [GRUESOME DETAIL WARNING] It was said that Griboyedov was promptly decapitated, his head displayed on a spike by a kebab vendor, while his body ended up atop a garbage heap after enduring three days of abuse in the streets [END OF GRUESOME DETAILS] As part of the reparation for Griboyedov’s death, Russia received the Shah diamond, which formed part of the Russian crown jewels until the Revolution, and is now displayed in the Kremlin. To be fair, some folks around this time did have some longevity, including those names most familiar to Western audiences. Tolstoy lasted until he was 82, while Dostoyevsky reached a more modest 59, his health having been impacted by five years of Siberian exile … because Russia.  The old lady in the "babushka" scarf in the background really sells this one The old lady in the "babushka" scarf in the background really sells this one

Aside from maybe Griboyedov, with all due respect to his accomplishments, the four I had mentioned were not some minor literary notes in the history of Russia, but were some of its biggest names, despite their untimely passing. The deaths of Pushkin and Lermontov in duels likely contributed to cementing the role of this honour dispute in Russian culture. I knew what a “second” was (the friend chosen by each of the duelists to assist them in the conduct of the duel) in Russian as early as ten years old. Whereas I’d hardly known what the term was in English until years after getting to Canada, and the only reason I even recognized it in context was because of its passing similarity to the Russian “sekundant”. It’s also why when I was watching Bridgerton and the dueling scene came up, I was bizarrely giddy with excitement before I realized I was just feeling nostalgic for a plot device I’ve hardly come across since my childhood (Hamilton musical excepted, of course).

As I mentioned at the start of this entry, there’s something peculiarly Russian about all this. The authors, much like many of their heroes, shone bright, died early and left a heavily romanticized corpse. Affairs of honour, diseases, mental illness – the darkness of the art that has become so associated with Russia is reflected in life itself, fitting for a country whose history can be summed up in the single sentence “And then things got worse.” It’s incredible how these people left such a mark on their culture in such a short amount of time, but if this is the prerequisite to being a successful Russian author, I’m going to have to take a hard pass and die in obscurity. Hopefully I can instead take a cue from the Russian people who’d made their name writing in English. Vladimir Nabokov’s 78, Ayn Rand’s 77 and Isaac Asimov’s 72 are not exactly impressive, but are far more palatable. |

Michael SerebriakovMichael is a husband, father of three, lawyer, writer, and looking for that first big leap into publishing. All opinions are author's own. StoriesUrsa Major Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed