Silver Wordsmith: An author's journey |

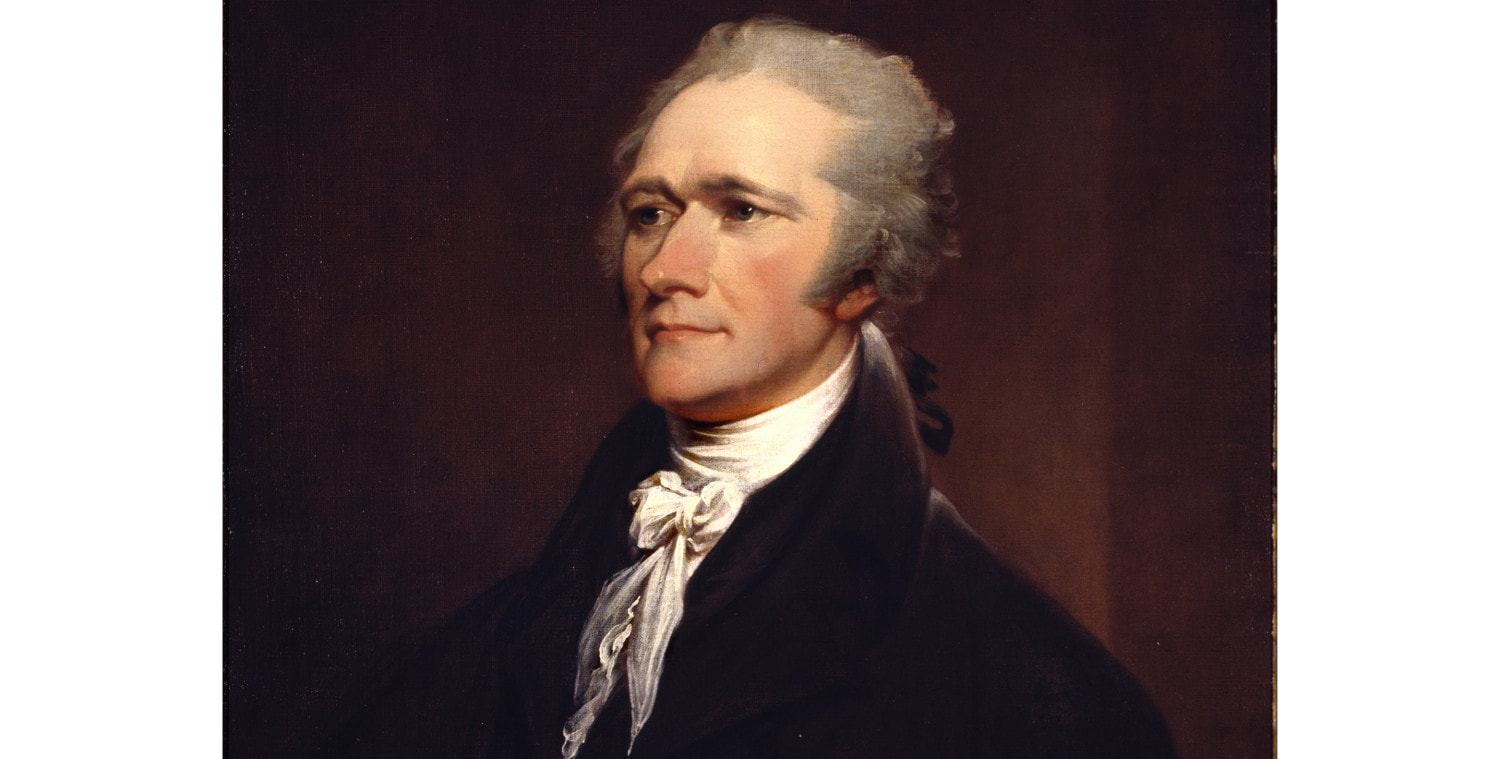

The Soviet-era apartment building at number 5 Yegerskaya Street in Moscow where my dad spent many of those years patiently waiting for destiny. Image credit to Google Streetview The Soviet-era apartment building at number 5 Yegerskaya Street in Moscow where my dad spent many of those years patiently waiting for destiny. Image credit to Google Streetview Alexander Hamilton was born in 1755 (or possibly 1757, such is the fickle mistress that is history where even the first line of a life ends in an asterisk) on Nevis in the British West Indies, to a father that abandoned him and a mother that died with Alexander in her arms. Alexander Serebriakov was born two centuries later in 1964 in Moscow, the Soviet Union, to a mother whose father abandoned her and a father whose own father went missing in action in the Second World War. These wisps of similarities are woven through all of us allowing us to find brotherhood across the centuries and continents. The two Alexanders combined for just over a century of life, forging in their own allotted halves of this time two very different legacies. In 2017, one Michael Serebriakov, born in 1986 in Budapest, Hungary, to two bright university students who had no idea what they were getting themselves into, had his life profoundly shaped by the two men. My father had a typical Soviet childhood. Both his parents were in the workforce so he was mostly raised by his grandmothers. But normality was tossed out the window for the rest of his life when my grandfather earned a foreign business post for three years in a port city on the west coast of North America. For a Soviet child, three years in Vancouver had turned his life upside down. Hamilton had a similarly transformative experience by sailing west. At the age of 17 (or 15, as previously mentioned) he arrived in New York to a country on the brink of revolution. It inspired a young mind to work for the prosperity of his nation, and his service during the American War of Independence and then in the cabinet of George Washington as the Secretary of the Treasury earned him the title of an American Founding Father and his face on the ten-dollar bill. My dad earned no such accolades, but he was no less of a dreamer that would beat a path to any goal he set for himself. After three years, when his father’s posting expired, he was told to let go of any fantasies that he may have indulged in. It was the mid-seventies, and a capitalist country was simply out of reach. If the three years felt like a dream, that’s because they were, and like with any dream, it was time to wake up. Stubbornness was a trait that came early to my dad, and he held onto to his boyhood fantasies. Vancouver was home. Canada was the place where he would forge his future. He held onto this for the 15 years it took for the Soviet Union to fall. And then another five years before he got a chance to vacation in Vancouver, revisiting all of his old favourite places with childlike glee. And then he took that determination into an immigration process that lasted three years. A quarter century after he was told to forget it, Alexander had moved his wife and two children to the country of his dreams, to the place he knew all along that their lives would flourish. He would be given less than twenty years to enjoy the fruits of his success.  What kind of twisted genius does it take to look at this man and see the most Hip-Hop of all the Founding Fathers? What kind of twisted genius does it take to look at this man and see the most Hip-Hop of all the Founding Fathers? My dad passed away in May of 2017, just days after his fifty-third party after a battle with cancer. And battle it he did until the very end, always trying to put his concerns for his family ahead of himself. One of the last coherent things he said was apologizing to my grandmother for leaving her daughter, his wife, all alone. That’s the kind of man he was. Full of caring for his loved ones, even if it that caring had the ability to overwhelm the object of his affection. Any way you spin my feelings, his death had left a massive crater in my life. Father’s Day came and went, so did the start of a new hockey season, and then the premier of the next Star Wars movie. Each jolt a painful reminder that he was gone. I spent months in confusing oscillation between grief and anger, with brief spurts of calm that would be quickly trampled by another gloomy stretch. Everything I had strived to improve in myself over the last few years fell completely off the map. I stopped writing, stopped exercising, stopped learning Spanish. I filled my time with junk like aimlessly scrolling reddit just to keep my brain from getting too stimulated. I had dug into my rut, and was quite comfortable in it, thanks very much. That had all changed because in 2015, Lin-Manuel Miranda, a New York-born composer, lyricist, playwright, and actor of Puerto Rican and Mexican heritage had premiered his newest musical based on the life of Alexander Hamilton. My awareness of Hamilton the musical trickled into my life slower than I would like to admit. Through some online discussions and articles I’ve heard whisperings of a musical that had cast a black person to play Aaron Burr. Knowing what I know now I think it’s a great disservice that that’s what was talked about, and not the entirety of the colour-conscious casting choices that were a big part of why the musical has become so inspirational. In early 2016, I missed the Hamilton question in the online Jeopardy audition test, not knowing which musical the song “The Election of 1800” appeared. Funny, two years later and I’m singing along to the words with my four year-old son. And then I saw it in the news again when the Broadway cast called out American Vice-President elect Mike Pence and his administration for the atrocious ideas that they represent. There’s really no excuse for me not to have gone off and learned everything I could about the musical at that point, but that’s neither here nor there, and it at least put it firmly on my radar at that point.  The man himself, Lin-Manuel Miranda performing as Hamilton. That hair though The man himself, Lin-Manuel Miranda performing as Hamilton. That hair though Fast forward to September 2017, when a series of events lined up in such a way that I had a lot of time during my morning commute, so instead of wasting it on whatever frivolities I was into at the time, I listened to the whole Broadway cast recording on Spotify. I never expected a piece of musical theater to blow me away but there I was, putting the soundtrack on at home for the whole family to listen to. My wife had already started doing so ages ago, because she’s generally ahead of me in these things, but now Hamilton was a real presence and even my son started saying no to the usual Disney playlist and insisting that we play Hamilton on repeat, even in the car. This all reached its crescendo in early November. It was about a week after my birthday, and the holidays were fast approaching while I sat under my own personal storm cloud feeling anything but jolly. I was working from home and in the other room I heard my son playing and singing, though in a voice that bordered on yelling: “Alexander Hamilton. Alexander Hamilton! ALEXANDER HAMILTON!” I thought had struck me. Internet searches were performed. Discussions were had. Questionable financial decisions were made. And suddenly my wife and I found ourselves in possession of two Hamilton tickets in Seattle in March. The Hamilton exposure at home went up. That entire weekend was spent listening to nothing but the soundtrack during any available moment. And then something happened. Something I didn’t notice until almost a month later. I brushed the dust off my unfinished short stories. I started playing catch-up in my Duolingo and Memrise apps. I read more diligently. I was able to focus more at work. Whatever inspiration was contained in the musical, and trust me, if you’ve listened or watched Hamilton you know inspiration is contained in every other line, it had awakened something in me. It began to clear the fog out of my mind. It set me back on my path and made me remember myself. The key to all of this isn’t even one of Hamilton’s lines, it’s one sung by Aaron Burr, delivered so powerfully by the talented Leslie Odom Jr. “I am the one thing in life I can control.” And so I did. The musical reminded me that for all of life’s unexpected setbacks, for all of its twists and turns and tragedies that lead men like Hamilton and my father to build legacies in lands so far from where they were born, one must never cede control. Alexander Hamilton fought against his political enemies, the most dangerous of which was probably himself. Alexander Serebriakov resisted the currents of history and kept his dream alive for his children. Both affected the world in their own unique ways. To my father, thank you for inspiring me to put family first. If there’s any piece of your complicated self I will carry forward with me it’s that. And to Alexander Hamilton, thanks for inspiring Lin-Manuel Miranda, whose efforts to present your life with a contemporary lens have given me the strength to carry myself into the years ahead.

0 Comments

Personify your fears so you have something you can picture when you’re curled up in a little ball and feeling like a complete failure. Photo credit: Tim Ellis on VisualHunt.com / CC BY-NC Personify your fears so you have something you can picture when you’re curled up in a little ball and feeling like a complete failure. Photo credit: Tim Ellis on VisualHunt.com / CC BY-NC

Despite having written for a long time, half my current struggle is not my writing itself but rather how I write. The most recent battle has involved starting my next novel project. My first and currently incomplete novel had finished its first draft stage two years ago. Since then, it has undergone one massive revision and is currently going through its second one. Editing is its own kind of challenge and reward but it isn’t as fulfilling to me as putting new words on paper.

I have been able to satisfy my appetite with a few short stories in the meantime, but I’m feeling about ready to launch into a new novel, and have spent months failing miserably at it. There’s close to a dozen ideas I’m itching to rip into, but I also have the approximate confidence of a field mouse staring down a parliament of owls. ​So what’s the problem? And I mean, other than the fact that I think my plots are a snooze-fest, my characters are flat and my prose is self-indulgent? Well, the problem is that in my mind none of those novels feel like they exist. I see them as nebulas floating in the cavernous universe of my mind, and once I try to distill them into something tangible I get a few drops, not the roaring hot ball of a star. The answer, according to my epiphany which like many of my epiphanies may turn out to be an episode of self-delusion, is outlining. I can’t not outline. And I hate it.

The answer, according to my epiphany which like many of my epiphanies may turn out to be an episode of self-delusion, is outlining. I can’t not outline. And I hate it.

But why hate it? Because like any writer, my mind latches on only to such evidence that can be used against me at times of insecurity. Take the following tweet from one of my most admired writers, J. Michael Straczynski, who played no small part in my childhood as the creator of Babylon 5 (seriously, free up your whole week and enjoy the ride if you can get your hands on this show):

My pride and, apparently, my shame. My pride and, apparently, my shame.

Now here’s someone who has come up with one of the most brilliant multi-season arcs of a TV show telling me he avoids outlining because his characters act on their own accord. In my situation, on the other hand, I feel like my characters are comatose unless the plot drags them kicking and screaming into doing something interesting. And then there’s an uplifting post on the New York Book Editors blog which gut punches you by telling you that “planning your novel ahead of time increases its likelihood of being dead on arrival†and that “the less you know before you start, the more you stand to uncover as you write.†So great, if I choose to outline, my novel will likely be a predictable limp fish that will likely be euthanized by discerning publishers. And then there’s the description of “Macro Planners†by Orange Prize winning author Zadie Smith, who says you will recognizes a writer who plans and outlines excessively “from those Moleskines he insists on buyingâ€. This seems needlessly personal: ​ So now that I’ve been officially relegated to a walking stereotype, why continue to rely on outlines? I certainly see merit in the argument that a robust outline takes some of the magic out of it – once plot elements and characterization has been summed up in bullet point form, it might feel like there’s nothing left to the process. Neil D’Silva went so far as to say that outlining “makes the writing formulaic and there’s no adventure left in it for me†So why do I insist on it?  Outlines and skeletons are similar in that they are both spooky as fuck. Photo Credit: Johnson Cameraface on Visualhunt / CC BY-NC-SA Outlines and skeletons are similar in that they are both spooky as fuck. Photo Credit: Johnson Cameraface on Visualhunt / CC BY-NC-SA

Because I’m not sure if I’m able to write any other way. Let’s take my first novel for example. When I first starting putting it to paper, I set out to write a longish short story. About 8,000 words in, and having barely scratched the surface of the plot, I found myself staring at a project I hadn’t anticipated. It grew in spurts and starts, climbing approximately to 25,000 over the course of the next four years. Not exactly the most efficient pace, is it?

And then, I decided to outline the whole sucker. I spent a few brainstorming sessions laying out the chapters, arriving at approximately 20, with a whole fleshed-out paragraph for what was going to happen in that chapter. And that’s when the ball started really rolling. I was able to focus on my present writing but keeping an eye to the future and the past. Sometimes when I was stuck on a current chapter, but inspiration struck for a later scene, I would skip ahead and start writing that out. It was great insurance against writers block. I had reworked my initial summary significantly, but I feel like that’s what really got me to the finish line. But that was just my first novel, right? Amateurish stuff where crutches are needed before I could learn how to be a proper writer? That’s what I assumed. So for my next project, I took an idea that had been percolating in my head for years – I had a vague plot outline for the work but it was entirely in my head. I thought it would be a great start. Over 5,000 words in and I’m convinced it needs to be burned with fire. Nothing has happened, the plot has barely trudged forward, and I personally want to strangle the main character to death. But maybe I haven’t gotten deep enough. Maybe the issue is I had that outline in my head and it’s stifling my creativity. So I tried again from scratch. Now I took something that was only formulated as a vague idea and I was about to write it furiously. I stared at the page for a half hour. Nothing happened. Then I tried with a different idea, and nothing happened. So what the hell? As writers, we’re all different, and we need to embrace those difference. Forget the hard and fast rules. The same Book Editors of New York piece also concedes that if outlines help get you started, you should keep them. And I think that part is key. The outline may be the skeleton of the work but the work itself should be organic. It should be a living creature that changes and evolves into something new. It could be a caterpillar that transforms into a butterfly but the blueprint for that butterfly was still contained in the caterpillar. I will probably share my exact outlining process in a later blog post, but I can already tell you these can come in various shapes and sizes. You can have a sheet full of bullet points that just keeps you on track. Or something that follows the rise and fall of all the plotlines to ensure they’re tied together. Or you can have an outline that sketches out the structure of the finished work in a very technical sense – a breakdown between three Acts, each occupying a certain percentage of the work (often 25/50/25), a major inciting incident, and the elegant sinusoidal curve of action that alternates between successes and failures. ​ A lot of great works can be broken down into this kind of structure, but then you’re faced with a chicken or egg problem – did we distill the structure out of great works with effective plot, or was there some kind of conscious or semi-conscious effort on the part of the authors to get their works there? The important lesson I had to learn with outlines is that’s it’s okay to rely on them. And it’s okay to wing it. It’s okay to be the writer you’re comfortable with being, because in that blanket of comfort is where your creativity will flourish. |

Michael SerebriakovMichael is a husband, father of three, lawyer, writer, and looking for that first big leap into publishing. All opinions are author's own. StoriesUrsa Major Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed