Silver Wordsmith: An author's journey |

It's a great movie poster because it accurately portrays how your brain feels when you read the book It's a great movie poster because it accurately portrays how your brain feels when you read the book To say that 2021 was not my best reading year would be an understatement – this was my worst reading year since 2011, when I’d graduated law school and moved back to Vancouver. I’ve talked about this before but a lot of it is pandemic related. Given that my primary reding time was during my public transit commute to and from work and because I’ve been working from home all this time, it’s been harder for me to find time to read. One of my New Year’s resolutions has been to try to get my reading more on track, so we’ll see how that goes. That said, I’ve read (and listened to, which I count as reading and will fight anyone who suggests otherwise) some great books this year. I ended up joining the book club that was organized at our housing cooperative and was exposed to novels I probably would not have turned to on my own. It was a great experience but by the of it, I had trouble keeping up and also with my poor reding schedule wanted to branch out into my own selections. There were a few other notable reading events that happened for me during the year that don’t quite make the last below including:

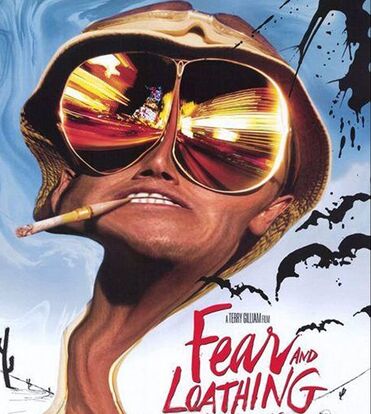

Thanks, but Let’s Not Do This Again Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas by Hunter S. Thompson. I suppose I could have used The Way of Kings for this one, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t talk about the absolute trip that was this novel. I had to actually stop in the middle of the audiobook to catch up my knowledge on its context because I needed to confirm how much of it was based on what actually occurred and how much of it was just inspired by true events. Turns out, Hunter S. Thompson wanted the book so accurate that he actually lamented mashing up two separate trips into one because he thought it hurt the authenticity of the narrative. To actually believe what was happening stretched the limits of my imagination, especially considering how horrible the two main characters were to a lot of the people they encountered along the way, but well, I guess that’s drug and drinking binges for you. In any case, it was a super fascinating window into a world so far removed from mine I’m not sure I’ll ever understand it, but I think one such trip is more than enough. Honourable Mention Sabrina by Nick Drnaso. Good heavens was this graphic novel ever a depressing read – from the heinous crime that launches the events of the book, to the various characters’ reactions to it to the crushing proliferation of conspiracy theories and how they affect the people closest to the events. The illustrations are also done in a particular style that minimizes the expressions of the characters which further adds to the sense of sadness and detachment that oozes from every page. As heavy as the book was though, I think it was also brilliant. That said, I think the only way I could read was the way I ended up doing – a few pages at a time. Most Fun Scott Pilgrim series by Bryan Lee O'Malley. I’ve read the Scott Pilgrim series before, about ten years ago when I used to live in Toronto where this graphic novel (or comic, whatever, labels are stupid) is set. I encountered a couple of Instagram reels about the movie recently and got nostalgic so decided to pick it up again. I feel like it’s got one of the best main character introductions I’ve ever read since basically on the very first page you’re told Scott is twenty-three and has a new girlfriend who’s still in high school. It’s like, “Yup, there’s Scott, he’s a giant loser by the way”. I’m already halfway through volume four out of six and having a lot of fun getting back into this world that is basically like ours except with certain video game elements woven into reality. I highly recommend the read, but the movie stars both Captain America and Captain Marvel so you could watch that, too.  Okay but this is *actual* poetry Okay but this is *actual* poetry Best Book of 2020 On a Sunbeam by Tillie Walden. There is not enough I can say here about just how much I enjoyed this book. In fact, I prepared a whole separate post to go on and on about how great it is, but for whatever reason I had neglected to publish it. It’s a science fiction graphic novel, though the soft sci-fi aspects take a back seat to the gorgeous art and touching story. I’m going to be rereading this one again and not that long from now I just known it. In the meantime, at the risk of going on too long about it here, I’ll just leave this as a placeholder when I finally post that full entry and link to it. Honourable mention: Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens. Funnily enough, I have the same deal with this one as I do with On a Sunbeam in the sense that the book struck me so much I went and wrote a whole post about it and then just never ended up publishing it. Again, I think I’m just going link to it when I finally do get around to posting it. What I do want to say is that this was one of our Book Club books, which again is why I’m happy I joined, and one of the books I really enjoyed with how much it got into the descriptions of the landscape and the local wildlife without losing sight of what is essentially a coming-of-age story with a background undercurrent of murder mystery that suddenly ramps up to such a pace that you find yourself surprised you can’t put the book down. I think that about wraps it up for this year. Here’s hoping for a more productive, but at least just as fun, reading year this year.

0 Comments

Late last week, literary Twitter exploded with one of the stupidest arguments that I’d ever seen and, as the Russian saying goes “a pig will find mud”, I decided to wade in.

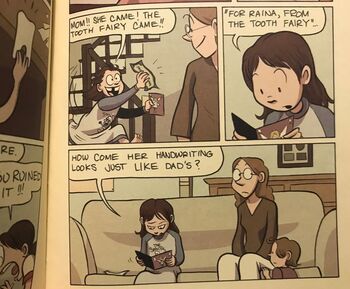

Apparently, what all the brouhaha started with was someone claiming that if the author hasn’t hooked them within the first 20 pages, then they immediately drop the book. Granted, this is a completely arbitrary cut off that doesn’t give legitimate slow burns a fare shake. I’m not going to defend this particular opinion. But the rebuttal to this that ended up getting retweeted into every corner of the universe basically said that not finishing a book is an insult to the author, and the least you could do is finish whatever you started. Of course, this is literary and writing Twitter we’re talking about, where people say the most asinine shit for engagement. My two favourite examples are “Am I the only one that gets excited when I sell a book?” and “My friend told me they think only people with blue eyes make good authors, do you agree?” However, this accusation of insulting authors struck the perfect balance between being outrageous, and sounding perfectly serious. That tweet really packed a two-for-one punch. Form the perspective of readers, it reeked of snobbishness – as if because you managed to commit to the whole of War and Peace after getting ten pages into, it somehow makes you a more respectful reader. All it does is further discourage those intimidated by such pieces of literature because it makes them feel like they’d be looked down on if they don’t end up finishing it. Well, if a cockroach looks down on you, does that really affect your day? And from the perspective of authors, this seems to have both arrogance and insecurity all wrapped into one – like a reader owes it to you to finish your book as long as they started it, and if they drop it, well, that’s not your fault, it’s the reader bestowing upon you a great dishonour. How utterly rude of them. Or you could think about it this way – at best, there’s no such thing as a book loved by everyone, or at worst, don’t write a garbage book and people might be less likely to put it down in the first ten pages. I really do have to hand it to that inflammatory – it was some kind of provocative work of art in its own right; based on a completely ludicrous premise. How would the author even know that I didn’t finish their book that I bought in order to even be insulted by me. The tweet managed to illuminate so many ugly opinions when it comes to reading. One rebuttal to people saying that their time is too precious to waste on books they don’t like was “Well if your time is worth so much to you, what are you doing on Twitter?” Apparently, we’re not allowed to have fun until we’ve finished torturing ourselves with hundreds of pages of writing we don’t want to read. It’s like if you went to a nice restaurant and your food came way too salty, and you didn’t want to finish it, and then I accused you of being rude to the chef, and you said “But I only eat food that is good” and my rebuttal was that I saw you eating at McDonalds last week. The amount of people who seemed to be extremely emotionally invested in how other people spend their time is astounding. Makes me think that it all boils down to some misplaced sense of superiority – these people don’t read books because they enjoy it or because they get something out of it, they read because they think they can lord it over someone who didn’t. “Well I am on a whole other level, for I have read Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment and you have not.” Well I read it in the original Russian, and it was an awful experience, so go hang out at the kids’ table you thought you were setting up for everyone else, and I’ll hang out with the people who don’t have sticks lodged up their butts. And this is coming from someone who insists on finishing every book he opens; not as a matter of principle, but more as a result of a deep person flaw. I just don’t think it makes a difference if you start ten and finish ten or if you start ten and finish one. Same as it doesn’t make a difference if you read two books a year, or fifty two, or if you’re reading genre fiction off the shelves of your grocery store, or the greatest Lithuanian authors of the pre-Soviet era. Read what you want, read what brings you joy, and don’t let any Twitter gatekeepers make you feel bad about any of it.  My kids almost got wise because of this page My kids almost got wise because of this page

You know what, as long as it’s still January, I’m allowed to do “Best X of 2020” posts. My house, my rules. That said, it feels weird using the word “best” and “2020” in the same sentence. Very little about 2020 felt good, and I noticed that this December I wasn’t inundated with the Top Countdowns for the year as is normally the custom. My guess is people don’t have the appetite for it, which is understandable. It looks like I didn’t either seeing as how I hardly noticed anything missing. That said, I’ve been doing my Writing and Reading wrap-up posts since I started this blog, and I don’t see the need to skip this year. It’s healthy to reflect on anything good that happened last year, though sometimes it feels like getting blood from a stone. Apropos of that last statement, this has not been a great reading year for me. For one, I lost my prime reading time, which was on my commute to and from work, due to working exclusively from home, which in itself had its own plethora of benefits, but its side effects as well. The other reason being like many people I just wasn’t in the right headspace to pick up a book instead of doomscrolling for a few hours before completely slipping into despair. Nonetheless, there were a few highlights from what I did read last year, so let’s jump into those.

Most Fun Smile by Raina Telgemeier. This was somehow my fourth Telgemeier book even though it was her first bestselling graphic novel, but it also has a special place in my heart, having picked it up for my kids at the airport during a short business trip. Felt like a very on-point dad thing to do – grabbing something for the kids while I’m away. My dad travelled a lot starting around the time when I was my eldest’s age, and he would do the same thing for us as sort of compensation for being away from us for days and occasionally weeks at a time. The book was not ideal for my four year-old but with the six year-old now in kindergarten, the graphic novel hit on a lot of points that have become a part of his life, like teasing, bullying, making friends and changing friends. The endearing art also goes a long way to packaging this coming-of-age work for young minds, and I’ve been catching the eldest flipping through his other Telgemeier books at his leisure. Thanks, but Let’s Not Do This Again Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick. I’ve read a bit of Dick before, with A Scanner Darkly being my favourite (it has a fantastic film adaptation as well), and hearing a lot of good things about the television show, I thought I’d check this out. Boy, was this a lesson in setting proper expectations. Let’s just say, even without watching the show, I can tell this is nothing like the show. The Nazi victory in the Second World War is less the driving force of the plot but rather the backdrop for an exploration of colonialism, destiny and hope. It is incredibly slow-paced if one is looking for a big thriller-paced payoff and shies away from really exploring the inherent atrocities of living under Nazi and Imperial Japanese occupation. There’s a lot to like about this book if one focuses on what it is trying to say, and not what you thought it was going to try to say, and the colonialism critique through the eyes of the colonized colonizer alone makes the read worth it. Lesson learned though about judging a book by its adaptation. Honourable Mention I’m Not Sick, I Don’t Need Help! by Xavier Amador. This was part of my research dive for my first novel – a book who’s intended audience is families of those who suffer from schizophrenia with a focus on one of its most insidious symptoms – the inability to tell one is suffering from a mental illness despite all rational signs indicating so. Equal measures informative and heartbreaking, it strengthened my understanding of the disease, but left me with a heavy feeling and a renewed sympathy for those taking care of loved ones suffering from this terrible affliction.

Most Influential

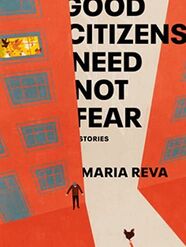

Good Citizens Need Not Fear by Maria Reva. One of the few times (if not the only time) I’ve ever pre-ordered a book because I was so excited by the prospect of reading it. It happened to arrive at the store just at the turn of the pandemic, which locked it up for a couple of months before I was able to get my hands on it. And when I did finally get a chance to go through it, it was well worth the wait. Not only was this a collection of short stories – the genre that launched my writing and which I still turn to from time to time – but it was also close to my heart in its setting. The series of interconnected stories follow a group of characters who at one point or another reside at a crumbling apartment block in Ukraine in the twilight years of the Soviet Union. It chronicles years I have lived through but was mostly too young to remember, though even for me that time forms an integral term of my early identity – political unrest, long lines for groceries, young parents not knowing what the immediate future will bring. It was a dying nation with a citizenry that had no choice but to live, and Reva’s short story collection captures this perfectly. It also illuminates for me a new perspective that I hadn’t spent enough time considering. As a third, or even fourth, generation Muscovite, there were certain privileges that my family had in the overall hierarchy of the Union, and I had rarely been forced to confront that colonialist reality in the way Reva’s satire made me do. So overall, the book was not only influential on me as a writer but as a person of Russian heritage as well. Honourable Mention Leviathan Wakes by James S. A. Corey (the first book in The Expanse series). I would be remiss if I didn’t mention an audiobook I listened to, mostly because I need to make my assertion that audiobooks are legitimate “reading” and I will fight anyone who suggests otherwise. My approach to this book was completely ass-backwards since I initially watched the first half of the first season of The Expanse and then, abandoned by the friends with whom I’d been watching, turned to the audiobook instead. I’m glad I did, because I’m not embarrassed to admit (that’s a lie, I’m really embarrassed by this) but I need more sci-fi on my reading list. For one, I’ve never had much of a yearning for hard sci-fi. I’ve always been a Star Wars, Babylon 5, Star Trek, space opera kind of guy with speedy interstellar travel, a whole host of alien races and a hint of the supernatural to keep things spicy. So The Expanse’s universe of limited technology, slow travel and murderous G-forces was not my regular cup of tea. That said there’s plenty to learned from someone else’s tea. It’s a great book, though it suffers from a diversity problem. The world is carefully crafted and believable and the terror of the supernatural element that is included is enhanced by this believability. Plus, since the travel and communication in my own story are far slower than any of the three works I mentioned, The Expanse offers me a lot of good tips. The adaptation seems pretty faithful too. Then again, that’s what I thought after the first couple of episodes of Altered Carbon, so don’t take my word for it.

Best Book of 2020

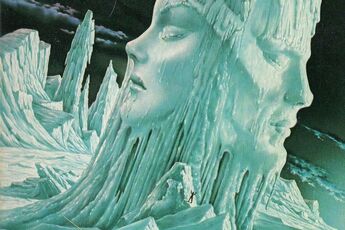

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott. Could I not have a chosen a book written this century? Or at least, the previous century? No, no I could not have. With the new movie having come out at the end of 2019 and my wife reminding me that this was one of her favourite books growing up, it seemed like the perfect time to pick this up and I’m so glad I did. It’s so infrequently that a book comes a long and endears me to the characters so much that I feel they’re real, and that I will actually miss their presence when they’re gone. I can see why the book has stood the test of time after more than a century and a half, with strong feminist themes and the perfect picture of the rewards and trials of family bonds. I will say that I’m still (as my wife) reeling from the whole Jo and Laurie thing, and I’m even madder about who she ends up with, but the movie did such a fantastic job of shedding new light on these plot developments I feel like it’s one of those rare adaptations that adds to the work instead of detracting from it. An added benefit was shining a light on the smooth-brains that criticized the film for being another retreading of the same thing (lovely as the 1994 film was, it isn’t even in the same league as this one). Apparently, these critics haven’t been witness to Sherlock Holmes being dusted off every couple of weeks, or just how much of our film and television entertainment is about watching men out-punch, out-spend and out-smart each other, and in the case of Tony Stark and Bruce Wayne, do all three. Everyone should read this book and watch the movie, it seems like one of those prerequisites to properly growing up. Honourable Mention The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin. I’ve rarely, if ever, felt such a strong urge to reread a book right after I’ve finished it. In the universe of the novel, Humans discover that the galaxy is populated by various subspecies of other Humans, most nearly indistinguishable from one other, with the most notable exception being those that reside on the aptly named chilly planet of Winter. Here, Humans don’t have a static biological sex but only exhibit sexual characteristics when they mate. The deep and intricate world and social commentary that Le Guin paints has so many layers it’s impossible to pick up on in a single read, and I feel like I should first consume academic literature on the novel before starting it again. It was very educational to see worldbuilding tied so inexorably to the themes of the book. Towards the end, a character who is used to the limited gender roles familiar to the reader remarks that is incredibly difficult treating these individuals as individuals, rather than as “men” and “women” – a comment on the reader who for hundreds of pages likely suffered from the same prejudices. Picking this book up was a concerted effort to familiarize myself with mid-century sci-fi and I hope I didn’t ruin the whole genre for myself by setting the bar too high. When I started writing my web serial The Bloodlet Sun in earnest is when I realized how difficult naming is in a sci-fi universe. It was one of the aspects of worldbuilding that initially held me back from sitting down and actually putting plot to paper and even when I bit the bullet the names still trickled out like molasses. And this doesn’t just apply to character names either. Every species and minor planetoid gets named only after an agonizing process that probably doesn’t need to be so agonizing, but that’s how I am. So I get that it’s difficult, and I get that certain shortcuts need to be made. Especially in something like Star Wars novels where characters hop from rock to rock at such a pace it’s sometimes hard to name that rock before they land on it. Recently I’ve been reading one such novel – Catalyst by James Luceno, which serves as a prequel to the Rogue One film and follows the rise of Orson Krennic and Galen Erso’s involvement in the Death Star project. I hadn’t grown up on Star Wars novels in general, so I don’t read them that often, but when I do, they’ve been a fairly enjoyable experience. As with any Star Wars writer, Luceno has the unenviable task of putting together a cohesive story that does not trample on any other established aspects of the Star Wars universe. To make the task easier, I found that most of the planets that serve merely as plot devices are created off-hand specifically for the novel itself, which means the author has quite a few planets they have to name without really needing to think of a long story or a full worldbuilding session. A good shortcut to do this is to find words that already sound natural in human language and provide slight modifications to them. Some examples from the more mainstream Star Wars universe come to mind – Luke’s home planet of Tatooine was named after its filming location of Tataouine in Tunisia. Mustafar, which is the lava planet that saw the true birth of Darth Vader, was likely inspired by “Mustafa” the anglicization of an epithet of Muhammad. In a less direct example from my favourite sci-fi series, Babylon 5, two species’ names bare a striking resembles to words existing in the English language. “Narn” is one letter away from “barn” and “Vorlon” is two letters away from “Gorgon”. Neither word is so similar to the original that it immediately invokes it, but both use structure already acceptable to the English-attuned ear. It makes sense to piggyback on existing words to create names for alien words without sounding like you’re trying too hard – something I think I still need to learn. But at the same time, one particular example in Catalyst I think went too far. Mind you, my bar when it comes to this kind of stuff is set fairly low. Only a couple of pages before the hard brakes on my immersion, the reader encounters a planet called “Kartoosh” – obviously inspires by the word “cartouche”, which is, honest to goodness, I’m still not sure what it is, but seems to commonly refer to a hieroglyphic depiction of a scroll. Oh, it was also a very mediocre 90s Eurodance group, which is how I first encountered the word. So for me, it wasn’t exactly an unknown entity, but the liberal change in spelling helped me move beyond that. That is, until I encountered the planet of “Samovar”. This. This is a samovar:  No it can't be, Nari, no it can't No it can't be, Nari, no it can't It’s basically a traditional Russian tea kettle. It’s like if your characters travelled to the planet “Microwave” or the city of “Colander”. Unlike with Kartoosh, there was no attempt to mask the origins: Luceno could have gone with “Samofar”, “Samobar” or “Zamovar” – all probably would have flown under my radar. Nope, it was just straight up “samovar”, take it or leave it. Unfortunately, my brain left it, and every time I read the planet’s name I giggled internally. Like I said at the beginning, I get it. It’s hard coming up with original alien names that don’t sound forced. But now every time I think back on this book I’m going to think of a massive ornamentally decorated kitchen appliance floating in space. So that’s a lesson learned for my own writing as well – there’s no problem with looking at someone else’s homework, but change a few answers to make sure the teacher doesn’t catch you cheating. When I set out to do this blog I hadn’t expected that my highest traffic would come from entries about my bullet journal (I use the term “traffic” very loosely – imagine a dusty country road which sees a couple of horse buggies and a pickup truck pass by every week). But it does seem that bullet journals, or “bujos” are still pretty popular and I’d be happy to share one of my favourite entries – my reading tracker: I always think it’s pretty self-explanatory until I show it to someone and they greet me with a “wtf” face, so I think this one needs a little bit of explanation. Firstly, the title “Kindling” is easy to miss since it runs across both pages both pages. This is a result of a very corny metaphor that came to me around the time I turned thirty (which is when I started my bujo) and refers to the fact that I think reading is the kindling that starts the mind’s fire. I’ve posted before about how important I think reading is to a writer, so this shouldn’t come as much of a surprise, though perhaps as an eye-roll moment. The basic premise of the entry is based on Tetris. Each colourful piece represents a particular reading medium (yes, I count audio books and will fight anyone who argues otherwise). Usually the threshold is about a half-hour of reading in the specific category, the notable exception being short stories where a single block represents a single short-story, even though it might take me anywhere between five and forty minutes to read one. The grey block that’s “blog/misc” is the loosest category, and I usually count this only if the reading is particularly involved or informative, but really it’s whatever I feel like (as you can see, I don’t often count it so it’s not exactly a “cheat” category). One of the wonderful things about the way this graph is set up is that I use it as a way of self-manipulation, specifically exploiting my competitive nature. It’s a point of pride for me to avoid any gaps between the pieces until the last possible moment and to leave as few as possible before the “play area” fills up. Based on this, not only do I sometimes need to read a particular genre or medium in order to make sure I don’t leave any gaps, but sometimes I intentionally place pieces in order to push myself towards doing something. For example, if I find that I haven’t read a short story or a graphic novel recently, I could place an audio book or novel piece in such a way that the only pieces that would satisfy the remaining gap are the short story or graphic novel blocks. Boom! Suddenly I’ve found additional motivation to reach for those. Not to mention what’s going on in the far right part of the player area, where I leave an empty single block wide column that’s quite familiar to Tetris players. The only way to fill this one is with my most often neglected medium – poetry. I’ve never been a poetry connoisseur, and most of it admittedly flies right over my head (feel like the proverbial swine before a whole pile of pearls), so I tend to steer away from it. That said, I do occasionally enjoy it, and I find it to be a valuable literary exposure, so I have to find ways to read it, or I will be left with an unsightly gap in my log. This has worked out great over the last couple of years as I’ve discovered that I quite enjoy the poetry of Pablo Neruda and Wisława Szymborska, and I’ve got a lot of others on my to-read list. A couple of interesting observations from the spread that I included above:

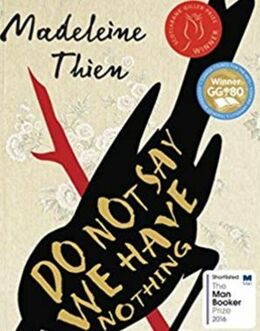

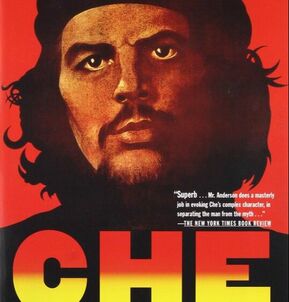

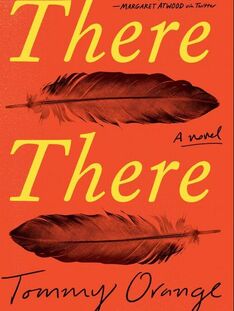

Definitely from the "excuse me, what the fuck?" school of book premises Definitely from the "excuse me, what the fuck?" school of book premises As mentioned in my previous entry, I wanted to start each year with a review of what I had written and what I had read in the previous year. Reading is essential to writing in the same way as eating is essential to living – it’s the kindling that goes into your head to start the fire of your own creativity. So I think as a writer it’s important for me to share not only what I read, but also describe ways in which it may have influenced me or helped me grow as a writer. Please don’t take this list as commentary on any books that don’t appear on it – as more likely than not, I simply had not read them. Most Fun Percy Jackson by Rick Riordan. I know I’m a little late to the party on this, but for this entry, I’m not talking about the best books of 2019, but rather, the best of what I read in 2019. One of the great things about having kids is being introduced to a fantastic world of children’s literature, and so the most fun I had reading this year were the first three books out of the Percy Jackson pentalogy. My wife picked this up for our eldest son earlier in the year and he was hooked. Between the non-stop monster appearance and the Greek mythology, it was everything his five-year-old mind wanted, and honestly my thirty-two-year-old mind was pretty impressed as well. I would recommend this for anyone who’s looking for a light entertaining read with lots of action and fun twists. I’ve gobbled up the first three novels of the series, and taking it slow with the other two, since my kid is still going through the fourth one. It encouraged me to also venture out into other books that are generally deemed to be for a younger audience, which has been very important in broadening my horizons. Honourable Mention Mortal Engines: Book 1 by Philip Reeve. Sometimes the core of worldbuilding is intricately constructed societies with attributes that subtly influence the plot in unexpected ways and often mirror our own world’s issues in a way that provides not too in-your-face commentary. And sometimes you have frickin' cities zooming around on wheels across a post-apocalyptic wasteland and eating each other. Whatever went into cooking up the core concept for Mortal Engines, I want some of that. I audiobooked this one and was treated to some hammy, but very appropriate narration from Barnaby Edwards. One particular thing about this book that I respect is that it did not pull any punches, and though it had dark tones throughout, not quite sure I was prepared for how this one wrapped up. Will likely steer clear of the movie because I hear it’s a stinker. Ditto goes for Percy Jackson, though curiosity may just kill the cat on that one. Welcome Discomfort The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas. This was basically the “it” book for a while, and for good reason. Though fictional, the story it tells might as well be looked at as factual, given the similarity it shares with countless incidents that happen in the United States and around the world. The use of first person present tense not only pulled me into the narrative but also gave me all the ammunition I need against anyone who claims that using present tense is doomed to fail. It allows the reader to walk a mile in the narrator’s shoes in a more intimate way, and while for many, the feelings it is meant to illicit are all-too familiar, for many others, myself included, it is meant to open eyes. Sure, for a lot of people who would benefit from a story like this, inherent biases will prevent them from picking it up, but the book’s existence alone, not to mention the powerful cultural impact it has already had, shows us the sustained power of novels in our society. A story that needs to be told, and a story that ought to change the world, no matter how uncomfortable it makes one feel about one’s privilege. Honourable Mention The Hunger Angel by Herta Müller. I picked this book up as part of my goal to sample the works of all Nobel Prize winners. Sometimes a pretentious-seeming exercise that occasional yields books I’m glad I picked up (see last year’s winner of That Was Fun but Let’s Not Do This Again). I’ve read a few novels about the horrors of the Holocaust, and a few novels that highlight the terror of the Gulags, but this work by a German author brought those two topics together for me. The protagonist is an ethnic German civilian living in Romania, who gets scooped up by the Soviet advance and is forcibly sent to a work camp in order to rebuild Soviet infrastructure destroyed in the war. As someone who had grown up in Russia, where WWII movies were a staple of daytime TV, to the point where something inside me still flinches whenever I hear German shouting, a small sinister part of me was tempted to revel in vengeance. A sort of “How do you like it now? At least your captors saw your death as a byproduct of their goals, not a goal unto itself.” Of course, every time this thought would rear its ugly head I’d smack it down. The German in question had nothing to do with any of the atrocities committed, yet is thrown into one of the most brutal prison systems known to history, where friends and acquaintances perish on a daily basis, and where the hunger angel rules as despot. Everything about this is fucked up, and was a system by which my immediate forebears benefited. If that doesn’t make one uncomfortable, nothing will.  Most Influential Becoming by Michele Obama. I am a sucker for self-narrated autobiographies and when that autobiography is by one of the most influential people of the decade, then this is something I can hardly pass up. I don’t follow American politics all that closely, but certainly maintain some exposure through news and the occasional meme whose origins I’m forced to look up. So purely from a curiosity aspect, seeing this influential presidency from an inside perspective was a learning experience. But what was far more significant for what it revealed about that part of the iceberg that lies brooding underneath the water. It demonstrated how the resolve of even a strong person like Obama is tested time and time again not only by the absurdity of the political machine by the racism and the misogyny baked directly into every aspect of our system. Ultimately, I find that this book is about strength; of will, of family bonds, of belief in oneself and one’s country, and should serve as inspiration to anyone who reads it. Honourable Mention An Unhinging of Wings by Margo Button. I found this collection of poetry as a recommendation in another book I read and it wrecked me, as it chronicles a mother’s struggles with her son’s schizophrenia, an illness that would eventually claim his life. This short collection is a tender work of absolute heartbreak – a mother’s ode to a son that had been taken from her. I’m not much of a poetry person, as most of it seems to go over my head, but this aimed directly at the heart – even now just thinking back on it I’m getting choked up a bit. It is a portrait of coping, of grief, an utterly private moment that was shared with the world, and I’m thankful to have had the privilege to read it. Thanks but Let’s Not Do This Again The God of Small Things by Arudhati Roy. First off, this was a fantastic book, as it’s Booker Prize win in 1997 would attest, but for some superficial reasons, it was a challenge for me to finish. The rich narrative that sometimes freely moves between time periods often slipped through my fingers, forcing me to sometimes reread whole paragraphs as I better understood their context. Same goes for the characters who are often introduced without much fanfare, and only pages later did I figure out where in the overall context they fit. Not to mention that the difficult scenes in this book make it really difficult to stomach, and this, along with Wide Sargasso Sea are the two books this year that forced me to put them down while my rage processed the actions of a particular character. In the end, I was glad I had read this book, but the lingering heaviness was difficult to shake off, and I’d rather not go through the profound sadness, discomfort and anger that it induces.  There's a reason this hood has become so recognizable - this is one of the most relevant books of 2019 There's a reason this hood has become so recognizable - this is one of the most relevant books of 2019 Best Book of 2019 The Testaments by Margaret Atwood. I hadn’t picked up anything by Atwood since I finished Maddaddam – the third book in her Maddaddam trilogy, and while it was good, it didn’t quite measure up to the series’ originator, Oryx and Crake, which is probably one of the most influential books I’d read. I had also raid the Handmaid’s Tale when I was younger, and possibly didn’t appreciate it as well as I could at the time. But boy did this one just blow me away both in terms of its writing style and its content. Atwood masterfully puts together an artful writing style that never descends into pretentiousness, which I find is often the sin of authors who take themselves too seriously. Instead, it’s crisp and punchy, which helps carry a narrative that keeps you on the edge of the seat with its excitement, while pushing you down into with its terrible plausibility. This is a book that came at exactly the right time – into a world that needs it. Laws, the constitution, ethics and morality are concepts that are worth only the people that choose to uphold them. When the collective consciousness chooses to abandon sanity, human rights become little but a paper shield. It’s a concept that bears repeating, because letting our guard down is what allows those willing to use this truth for their purposes to succeed. The Testaments should be required reading for this new decade.  Just look at all the accolades Just look at all the accolades Honourable Mention Washington Black by Esi Edugyan. In any year when I didn’t read The Testaments, this would have probably been my favourite book. Winner of the Scotiabank Giller Prize, short-listed for the Book, this was definitely the pinnacle of Canadian lit for 2018. The themes are carried masterfully by characters that feel real despite the occasional fantastic elements of the story. It was one of those books that made me look forward to the next opportunity that I can pick it up. What I found particular striking was Edugyan’s punching physical descriptions of her characters – using two or three sentences to paint a vivid portrait of a living being. The narrative absolutely gripped me until about the last twenty pages, when I ended up disagreeing with how the book wrapped up. This doesn’t often happen to me, and honestly is just probably simply the result of how invested I felt in the book. So proud to have such a powerful work be produced by a British Columbia writer. I find that I don’t talk enough about the stuff I read. Other than the review of my 2018 reading list in January, I don’t think I’ve mentioned it much, even though I have repeatedly said how important I think reading is to being an effective writer. So I thought I would therefore take a moment and talk about a novel I recently finished and that had more profound effect on me than I had expected.

Wide Sargasso Sea is a 1966 novel by Dominica-born British author Jean Rhys, and acts as a kind of prequel to Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre. I’m about to delve into some heavy spoilers for Jane Eyre so consider this your fair warning. I had read Jane Eyre when I was undergrad, and recall not particularly enjoying it. I much preferred the works of Jane Austen, and didn’t much care for the gloominess of Jane Eyre, though I suppose that was kind of the point of the genre. In any case, I knew what I was reading was good, but it wasn’t my thing. What did leave a big impression on me was how much I despised Rochester, the main love interest and the man Jane ends up with in the end. I couldn’t stand the archetypal brooding dark male lead, essentially the human equivalent of a wang-shaped monument to 19th century British patriarchy. And the cherry on top was that he kept his mentally ill wife Bertha locked up in the attic, which given the state of mental facilities in England at the time may or may not have been a mercy, but that’s besides the point. Mr. Darcy he definitely was not. So what Jean Rhys gave us in Wide Sargasso Sea, is the back story of Bertha (nee Antoinette) and a whole pile of reasons to hate Rochester even more. The novel follows Antoinette’s story – her childhood and adolescence in Jamaica, eventual marriage to Rochester and her precipitous decline into the mental state we witness in Jane Eyre. Antoinette is presented as someone who is able to rise above tragedy – her family estate is burned down (the colonial aspects of this book are problematic, but it was written in the sixties, after all), her developmentally delayed brother dies in the fire, her mother suffers a break and then dies alone as Antoinette is raised in a convent. Now into her adulthood, she’s ready to reconcile all that has happened her and make the best of her life in Jamaica along with her remaining friends and servants (there’s that colonialism poking its ugly head out again). But then comes Rochester, here presented as a younger brother who’s unlikely to get a sniff of the family fortune so he’s shipped off to the West Indies to marry rich. It is exceedingly easy to dislike Rochester from the get go. He is whiny, he is suspicious, he is racist, he will literally complain about anything including that the plants are too green. He marries Antoinette, somewhat reluctantly, and shockingly he never once complains about the fat dowry, though his endgame remains largely unclear. Here’s where I start going into some spoilers, so even though the end of the novel is a foregone conclusion, if you want to maintain some mystery, you can skip to the last three paragraphs of this entry. Though Antoinette also had her own major reservations about the marriage, she approaches it with her usual attitude of making the best out of her lemons, and she develops what appear to be genuine feelings for Rochester. Her husband, a suspicious man who thinks even the wilderness is out to get him, in turn eats with a spoon any vile rumor he hears about his wife and becomes convinced he’s been given “tainted goods”. Considering he never truly treats Antoinette as a human, this is a disturbing but apt description of his thoughts. Despite the already less-than-flattering portrait the novel had painted of Rochester, there was still room for more outrage. In fact, at one point I had to set the book in my lap and stare out the bus window before I could regroup and tackle the conclusion of the novel. Rochester fully embraces believing nothing but the worst about his wife, and channels all his feelings into vindictive rage. He basically attempts to write the textbook on gaslighting, choosing to call her “Bertha”, also one of her given names but one she does like using. He just flat-out states she’s more like a Bertha, and her opinion on the subject of how others should refer to her doesn’t matter. A theme that seems to resonate quite loudly in modern times as well. Oh, and did I not mention that he also sleeps with one of the servants while across a thin partition from his ailing wife, and then basically chocks up anything she does in response as an overreaction. Yeah, he’s swell. Rochester’s completely demented obsession to hurt Antoinette can be summarized with the following quote: “She’ll not laugh in the sun again. She’ll not dress up and smile at herself in that damnable looking-glass. Vain, silly creature. Made for loving? Yes, but she’ll have no lover for I don’t want her and she’ll see no other.” That has to send a chill down your spine. Not laugh in the sun again? This paints Rochester’s motivations to lock her up in the attic as a direct attempt to destroy her humanity, to deprive her of simple joy because he can and because he feels justified. I know Brontë did not intend for him to have such a dark backstory, but Rhys’ version of the character fitted in so perfectly with my own abysmally low opinion of Rochester, that the two have been inexorably linked in my mind. As far as I’m concerned, this is Rochester. Wide Sargasso Sea is also a perfect illustration of the importance of the public domain. While something like Pride and Prejudice and Zombies is awesomely creative, its mostly a vehicle for light entertainment (not that there’s anything wrong with that, I’m a strong proponent that there is little distinction between entertaining art and “arty” art) and doesn’t necessarily transform the original work. But in this case, it’s such a meaningful expansion of the story – bringing to light a character shrouded in darkness and casting into darkness a character that was supposed to provide the heroine with light. I’m glad I picked up Wide Sargasso Sea and I would recommend it to anyone who’s read Jane Eyre, especially Rochester-haters like myself.  How can you not read a book in which Santa looks like this? Credit: William Joyce How can you not read a book in which Santa looks like this? Credit: William Joyce Those of you who have been following this blog for a bit know that I’m still trying to figure out how best to use this resource. Which made me consider that even though I have expressed how important I think reading is for a writer, I haven’t said much about what I personally read. So I thought this would be a perfect opportunity to share, and given that it’s still early in the year, and I have already expressed how obsessed Russians are with their New Year’s stuff, I would put together a “Best of” list for 2018. To start with a disclaimer, I want to say that due to work and home commitments, 2018 has been my worst reading year in about five years, so I won’t provide my embarrassingly short list of everything consumed and will try to conceal it as best as I can. I’m also one of those people who doesn’t care to distinguish between audiobook and written text. Sure, you’re technically not “reading” but you’re still consuming stories in a way that’s closer to reading than say, observing drama or television, so I think it counts. Having said that, I probably won’t be mentioning below which is which unless it’s relevant to my feelings on the book. Anyway, without further preamble, here are some of the top books I’ve read in 2018: Most Fun Kingkiller Chronicle Day Two: The Wise Man’s Fear by Patrick Rothfuss. Earlier this summer I joined the legions of fans who are patiently waiting for the next book in the Kingkiller Chronicle saga. Fortunately, since my entry into this club is fresh, I am yet to join the other legions who are impatiently waiting for next one to come out. Either way, after taking several years to go through all the Song of Ice and Fire books, Kingkiller Chronicle is a refreshing read that doesn’t dwell on the doom and gloom. The world and character building is so detailed, however, that the pace of the books makes me think they need about 20 books and 200 years to finish. That said, despite the fact that I got myself into this fandom mess, I loved listening to this during my morning bike rides and runs. And knowing that Lin-Manuel Miranda is involved in an adaptation makes me all sorts of giddy for many reasons. Honourable Mention: Nicholas St. North by Laura Geringer and William Joyce. Ever just see a book in a store and then tell your friends how ridiculous you thought it looked and they bought it for you for your birthday because they knew you secretly really wanted it? Well that’s how this children’s novel came into my possession and I’m so glad it did. It’s the adventures of young Santa Claus in the days that he could be described as a “ruffian” and a “thief”. How could you not want to read this? It’s the first book in the whole Guardians of Childhood series and I’m not sure I’ll be picking up any of the sequels, but at the same time I had fun with the ridiculous premise and jaunty execution. Could have foregone a full two-page spread crapping all over my ancestors, but that’s beside the point. The Book was Better Altered Carbon by Richard K. Morgan. This was one I listened to on Audible and I think the experience was enhanced by Todd McLaren’s gruff narration of this hard-boiled detective novel placed in a sci-fi setting with excellent worldbuilding. The core concept of the novel, where human consciousness can be transferred to a variety of physical bodies, or “sleeves” thereby creating near-immortality, is taken to some very interesting places by Morgan. The Netflix adaptation, which I still think is a decent piece of television, tries to both condense and expand on parts of the story with varying effects. Overall I think the changes in the adaptation lead to a more sloppy plot with holes and inconsistencies, so I would recommend giving the book a try first.  This book racked up some serious accolades but really it was some high-level torture of the soul This book racked up some serious accolades but really it was some high-level torture of the soul That Was Fun but Let’s Not Do This Again The Stone Raft by Jose Saramago. Once upon a time, sometime in undergrad, I set myself a goal of sampling the work of each winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature. What I was doing making such lofty goals when I couldn’t even keep up with the assigned reading in my English classes I’ll never know, but more than a decade later I’ve just cracked 25%. The thing about winners of the Nobel Prize, is that it the Prize itself has been criticized for picking obscure winners that are less than accessible to the general public. I’ve found my experience to be a mixed bag – I absolutely fell in love with the poetry of Tomas Transtromer but getting through Mo Yan’s Republic of Wine felt a big like running an uphill marathon drunk. Stone Raft, by 1998 winner Jose Saramago would fall somewhere in the middle of this scale. On the one hand, I quite enjoyed all the satire that grew out of the Iberian Peninsula’s sudden break-off and drifting out to sea, as it took digs at tourism, international and local politics and nationalism. On the other hand, his paragraph-long sentences and dialogue structure that’s presented in a single sentence with only commas indicating a change of speaker, was a challenge to say the least. Not to mention the multiple references to outdated gender norms which may or may not have been part of the satire but sometimes it’s hard to tell, you know. In the end, it was a book I was glad I had read. I don’t believe I’ve read anything by a Portuguese writer before, and it was nice to dive back into some magical realism while I myself am somewhat exploring the genre. Honourable mention: Do Not Say We Have Nothing by Madeleine Thien. First off, this was an excellently written and deeply powerful novel with intricate characters that really brought the pain of their time to the surface. Well deserving of the Scotiabank Giller Prize that Thien won in 2016. So what exactly is my beef with it? The Cultural Revolution is downright terrifying. The ability of humans to turn on their neighbours, friends and even family in the name of survival is nearly limitless. And governments built on ideology, greed and a thirst for power can exploit that ability with frightening efficiency. So much of our western media, and particularly a relatively recent wave of young adult novels, portrays the eventual triumph over oppressive regimes. But if you want to read about hope dying under the treads of a tank, read Do Not Say We Have Nothing. For me, I’m going to take a short break from the bleakness of reality.  I've spent more than a year discretely hiding this very in-your-face cover on the bus. Though it was a university bus so I probably fit right in. I've spent more than a year discretely hiding this very in-your-face cover on the bus. Though it was a university bus so I probably fit right in. Most Influential Che: A Revolutionary Life by Jon Anderson. Yes, probably the most “wtf” entry here. I’ve had a fascination with Cuba ever since I was a little kid, having visited a couple of times while my grandparents were stationed there during Soviet times (yeah, a whoooole many more stories coming out of this that I’ll save for later). So as part of my education on the subject I wanted to know a bit more about the Cuban Revolution’s most far-reaching figure. Some paint him as the devil, others as a saint, and I wanted a book that can do a good job of showing me where the middle was. Ultimately, the safest word you can use to describe Guevara is “complicated”. He led a fairly inauspicious life that blew up to global significance within a few short years. He somehow possessed a poetic love for humanity while also being completely numb to the value of individual lives when they face off against his political ideals. He managed somehow to both be a visionary and someone who often went way in over his head which resulted in disastrous consequences for millions of people. As you can see, there’s lots of aspects of Guevara that can be picked apart into various fictional characters, and I’ve already begun the process with some of my works in progress. So at least in that respect I’m glad I read this. As an aside, reading this book on and off over the last year also made me realize how important reading fiction is to my writing, and you can read more about that here. Honouable Mention: Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow. The really influential thing here is actually the Hamilton musical, but I think Chernow’s voluminous biography rounded out that experience quite nicely.  Just go and read it, you won't regret it. Just go and read it, you won't regret it. Best Book of 2018 There There by Tommy Orange. For a few years now I’ve attended the Vancouver Writers Festival. Not only does it encourage me to buy books I normally wouldn’t have picked up, but also sometimes I buy a gem like this one. It’s been a while since I read anything that felt like a true page-turner for me, probably The Golden Compass, but this one I was just hooked. The interconnected stories of Native American characters living around the Oakland area pulled me in and wouldn’t let go. It was such a richly varied cast that it made me feel almost as though I was there, observing both the struggles with things like depression but also the hope that is built from family and community. The novel of course touched on sensitive issues that I can’t even begin to understand, lacking the perspective being a non-white minority as well as the original settlers of the land upon which white settlers built their country. We face very similar but somewhat different issues in Canada and our own Indigenous population is probably the most marginalized in our society. Admittedly, I’ve been on my own slow journey to understanding that is still far from complete, but I’m glad for books like this because they showcase how important novels are in changing the world. |

Michael SerebriakovMichael is a husband, father of three, lawyer, writer, and looking for that first big leap into publishing. All opinions are author's own. StoriesUrsa Major Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed