Silver Wordsmith: An author's journey |

|

Boro hovered patiently trying not breathe too loudly behind the Head Engineer.

“You’re not going to leave before I allow Maggie access back into my systems, are you?” Aimi asked without looking up at him, fingers busy at the console. “I know this is an unusual situation for you, and if I was in your place, I’d have some choice words about the Navy too.” Was it possible to see someone rolling their eyes while looking at the back of their head? Boro shrugged and pressed on. “But first and foremost, this is a military ship.” “Spare me, Commander. I’ve had the pleasure of talking to Captain Pueson and I don’t need him to send an echo up here.” Boro realized this was the longest she had kept still, but just as the thought passed through his mind, she was on the move again. “On the books, the Forseti is a research vessel. As far as its organized, the Forseti is a research vessel. In its mission, the Forseti is a research vessel. But then there’s the command crew, and don’t get me started on your little weapons dungeon which frankly the less I know about, the better I feel. Why a research vessel needs to be armed as if we’re going to fight off the entire Empire by ourselves is – anyway. At the end of the day, I make sure you have air to breathe, I make sure you have running water. My team and I are busy getting the ship where you say we need it to go, and making sure that no one sees it while we’re getting there. But what do I know? I’m just a lowly civilian,” she gave him a cruel smile. “I’m not invited to the officers’ table and yet I’m supposed to accept being bossed around by a glorified personal organizer.” “Is that what this is really about? A seat at the table?” To her credit, Aimi did her best to hide that she was grinding her teeth. “What this is about, Commander.” Never before had his title sounded so much like some sort of derision, “is that it’s my job to make sure the ship doesn’t come apart at the seams. And you need to do a better job of making sure the crew doesn’t do the same. You can let Maggie know she can have full access again, but from now on, this is a partnership. Not a chain of command. Understood?” Boro’s mind was torn between having to acquiesce to the ultimatum and repeating Pueson’s words about the Forseti being first and foremost a military vessel. Both options seemed to lack the nuance that recognized that the Forseti was, on the books, a research vessel; a research vessel that was outfitted with what Aimi had so lovingly referred to as “the dungeon”. “I will speak, to Maggie.” His response, spoken coolly despite the pounding he felt in his temple, didn’t satisfy him, but it at least left him in the position of a benevolent compromiser. Whether that registered with the Engineer remained a mystery to Boro, since without any kind of acknowledgement or even a nod, she returned to her work. --- Back on the bridge, it took Surch one look at Boro to say, “I see that went well.” Boro wanted to laugh it off, but everything in his head sounded clumsy and peevish. “To Ishikawa’s credit, she runs a tight ship, even if we’d apparently failed to provide one.” “What’s that?” Surch asked. “I’ll fill you in later. The important thing is to remember that it’s expected that our civilian crew will have some adjustment difficulties, but it’s in everyone’s best interests to cooperate.” As he said this, he cast his glance over to Maggie, who stood in the same leaning position she had been in when he left. “I take it the threats against my life have been rescinded?” She asked. “In a manner of speaking.” “Good. I like Ishikawa. She knows her ship.” “Our ship.” “Of course,” Maggie answered with a vague smile, “it’s ours.” She then placed her left hand, the one with lighter grey veins running through her otherwise deep brown skin, over five circular holes in her console, each only a few millimetres in diameter, and metallic tubes wriggled from between her nails and each of her fingertips and inserted themselves into the entry ports. --- Most of the time, the galley was a fairly deserted place, with only a handful of people in it a time, but there were peaks, especially between shifts, when as much as half the population of the ship ate and drank together, their chatter melting together into a cheerful din. For whatever reason, though he had struck Boro as a largely solitary creature, the Thorian preferred to make his appearances during these times. Perhaps he derived a sort of pleasure from the reactions of some of the crew that filtered towards him through the room, which wouldn’t have surprised Boro, because who knew what these Thorians truly derived their pleasure from. So it caused little surprise, but no small amount of irritation, when the Thorian deigned show up during the last such peak before the start of the next stasis rotation, which was about to effectively deprive the Thorian of his audience for a week. Most heads perked up at his entrance, faces adorned with a mix of idle to disgusted curiosity as well as freshly-sharpened eye daggers being sent towards the door of the galley. Head Engineer Ishikawa and Dr. Sufai, who often sat at the same table, were some of the few that hadn’t bothered even looking up. The deliberate scrape of three chairs across the floor made Boro shudder, not entirely from the sound. Meslina, a junior engineer named Eframe Gonsyn, and the Nabak all rose. They left behind plates of unfinished food and headed for the galley door.

0 Comments

There was some sort of occupational requirement for Techevers to be a bit different. A generous way to describe them would be ‘loopy’; however, Boro suspected that “absolutely unhinged” was a more appropriate label. And though some of the kinks have been worked out of this experiment that was now in its second decade, as self-induced attrition among them was at an all-time low, Boro still believed they were largely a hindrance, rather than the promised ultimate link between human and machine.

Boro took a deep breath and cocked his head to the side. “Okay Maggie, you’re going to have to walk me through this one.” “Very well. Engineer Ishikawa made it very clear that if I go rooting around her systems again without her permission, that she will personally, and I quote ‘Rip all those little dangly things from my fingers and shove them all the way – ’” “Thank you, Maggie, that’s enough.” “Are you sure? It went on for quite some time and I’ve got it all pretty much committed to memory.” “No, that’s alright.” “Too bad. Aimi has a fantastic command of language and an absolute arsenal of synonyms for various body parts.” Boro had no answer but threw back a pleading look at Surch, who shrugged and said, “That sounds like your bread and butter, Commander.” --- When he entered the engine room, nothing told Boro that anything was out of the ordinary. Aimi moved in fits and spurts, punching at buttons in a way that put about five times more wear and tear on them than necessary, but this was standard operating procedure for the Head Engineer. The engines themselves hummed away peacefully, stretched along either side of the room. As Boro walked between them towards the back of the room where the reactor was located, Aimi continued to ignore him as the two other engineers on duty cast furtive glances between him and their boss. At the heart of the reactor stood a translucent chamber where, suspended at its centre, was a black glassy ball about the width of Boro’s thumbnail that not only provided the ship with power but also the necessary touch of inexplicable magic needed for it to skim the surface of subspace at speeds that were magnitudes above the speed of light. When he leaned in to take a closer look at the quivering shadow that enveloped it, Aimi appeared behind him and asked, “Surely, we shouldn’t have to expect an inspection every time there’s a minor hiccup down here?” “Inspection?” Boro feigned surprise with two innocently raised eyebrows. “I’d think of it as more of a house call.” “Whatever you prefer to call, I think it hardly warrants any attention.” “And what is ‘it’, exactly?” “Just the drop being temperamental, nothing new, especially with this one.” Aimi threw up her chin in the direction of the black sphere behind Boro. “How do you mean?” “I don’t know where it’s been repurposed from, but it’s seen some things over its lifetime. Not sure who in their right mind thought that it was a good idea to make it power a skimmer and keep the ship ghosted for several months at a time. It acts up here and there, so I’m forced to make decisions as to what bears the brunt of its moods. And considering that the ghost is what’s keeping the ship alive, a figured a little drop of speed would be nothing to write home about.” Boro’s lip curled into the start of a smile, wondering how it was that the time Aimi and Surch were evidently spending together had slipped past his attention. “Maybe we could have skipped this whole conversation if you allowed Maggie to do her job,” Boro suggested. “Ah, so that’s why you’re here.” Aimi, as if having completely lost all interest, continued her rounds of instruments and displays. “I hear there may have been an exchange of words.” “In all fairness to Maggie, it was a very one-sided exchange.” “I figured,” Boro said with a smirk that must somehow have been audible since Aimi wheeled on him. “Commander, maybe it’s easy for you, squirreled away on your bridge, to forget what’s going on elsewhere on the ship, but from where I’m standing, it’s hardly pretty.” Her glasses slipped down a slightly long pale nose, the lights of the engine room accentuating the hard set of her jaw. “Some genius, in the Navy, mind you, these are your friends here, gave us a drop that’s more fit to power a very large toaster instead of an ORC starship. Some other genius, or maybe it’s the same genius, decided to give a Thorian free reign of the ship. My second’s a Nabak, gitang it, how do you think that affects him when that smug bumpy-headed asshole pokes his head in? And on top of that, no matter what I’m doing, no matter what I’m in the middle of, I’ve got that Techever rooting around in my systems, telling me how to do my job.” Boro barely opened his mouth to speak when Aimi put up her hand, her fingers spread. “I know they’re the Navy’s favourite toy right now, but I’ve never worked with a Techever before. No one even bothered to tell me there was one on board this ship until one day Maggie calls down and tries to tell me how to run my engines. Commander, I’ve been an engineer on a comet chaser that was basically just cobbled together spare parts and I feel like that was run better than the Forseti.” “I think you’re exaggerating.” “Well if you’re finding nothing unusual, then I’m really concerned about the state of our Navy.” She turned away before she finished her sentence, and Boro followed her silently as she walked to a panel at the opposite end of the engine room and started typing in commands.  One Pushkin's other great cultural contributions was wicked sideburns One Pushkin's other great cultural contributions was wicked sideburns

Recently I was doing some preliminary research for a future project that’s currently in the “dream” phase, that is, it’s not a full-fledged project that will currently take up time (as I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, I just added a new work to my plate and even I’m not so deranged as to spread myself even thinner). This particular line of research led me to 19th century Russian literature where I discovered a curious but quintessentially Russian pattern – in order to be a great Russian writer in the 19th century, all one had to do was die.

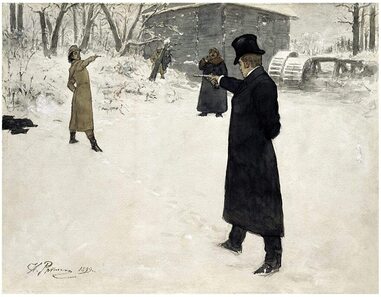

Some of these names won’t be familiar to you. Western readers tend to focus on those that were prolific towards the end of that century, like Tolstoy, Dostoevsky and Chekhov, but some of these names are bigger in Russia than even the three I mentioned. Alexander Pushkin, for example, is considered by most to be the greatest Russian poet and the founder of modern Russian literature. He’s a household name with a multitude of statues honouring him. Yet, he had died at the ripe age of 37 in 1837, shot in the stomach during a duel (the 29th of Pushkin’s career) by a man allegedly trying to seduce Pushkin’s wife. Mikhail Lermontov, the greatest figure in Russian Romanticism who carried the mantle of Russia’s greatest poet after Pushkin’s death did so for only four years, dying at the age of 26, also in a duel. Apparently, he had teased one of his military cadet school friends so mercilessly over his attire that the man, despite likely having the knowledge that Lermontov planned to throw away his shot, still shot the poet through the heart.  When you've lived longer than the two greatest Russian poets combined When you've lived longer than the two greatest Russian poets combined

No less tragically but far less colourfully, the previously mentioned Chekov died of tuberculosis at age 44. And Nikolai Gogol, the author of Dead Souls, one of my all-time favourite novels, passed after refusing food for nine straight days amidst a struggle with mental health issues and a crisis of spirituality. He was 42.

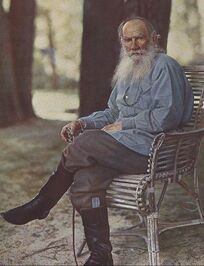

The worst fate of the lot befell Alexander Griboyedov, one of Pushkin’s mentors and Russia’s appointed ambassador to Iran. After Griboyedov provided sanctuary to several Armenian slaves who had escaped a harem, a frenzied mob broke into the embassy and murdered the Russian ambassador [GRUESOME DETAIL WARNING] It was said that Griboyedov was promptly decapitated, his head displayed on a spike by a kebab vendor, while his body ended up atop a garbage heap after enduring three days of abuse in the streets [END OF GRUESOME DETAILS] As part of the reparation for Griboyedov’s death, Russia received the Shah diamond, which formed part of the Russian crown jewels until the Revolution, and is now displayed in the Kremlin. To be fair, some folks around this time did have some longevity, including those names most familiar to Western audiences. Tolstoy lasted until he was 82, while Dostoyevsky reached a more modest 59, his health having been impacted by five years of Siberian exile … because Russia.  The old lady in the "babushka" scarf in the background really sells this one The old lady in the "babushka" scarf in the background really sells this one

Aside from maybe Griboyedov, with all due respect to his accomplishments, the four I had mentioned were not some minor literary notes in the history of Russia, but were some of its biggest names, despite their untimely passing. The deaths of Pushkin and Lermontov in duels likely contributed to cementing the role of this honour dispute in Russian culture. I knew what a “second” was (the friend chosen by each of the duelists to assist them in the conduct of the duel) in Russian as early as ten years old. Whereas I’d hardly known what the term was in English until years after getting to Canada, and the only reason I even recognized it in context was because of its passing similarity to the Russian “sekundant”. It’s also why when I was watching Bridgerton and the dueling scene came up, I was bizarrely giddy with excitement before I realized I was just feeling nostalgic for a plot device I’ve hardly come across since my childhood (Hamilton musical excepted, of course).

As I mentioned at the start of this entry, there’s something peculiarly Russian about all this. The authors, much like many of their heroes, shone bright, died early and left a heavily romanticized corpse. Affairs of honour, diseases, mental illness – the darkness of the art that has become so associated with Russia is reflected in life itself, fitting for a country whose history can be summed up in the single sentence “And then things got worse.” It’s incredible how these people left such a mark on their culture in such a short amount of time, but if this is the prerequisite to being a successful Russian author, I’m going to have to take a hard pass and die in obscurity. Hopefully I can instead take a cue from the Russian people who’d made their name writing in English. Vladimir Nabokov’s 78, Ayn Rand’s 77 and Isaac Asimov’s 72 are not exactly impressive, but are far more palatable.

What Boro did know, is that Drain Vortexes were, by and large, a useless cosmic phenomenon. Appearing within or around the Known Reaches once every twenty or thirty years, they allowed for well-shielded ships to travel through them over great distances in a fraction of what it normally took, which on the surface sounded appealing, but the wormholes usually led to some random desolate spot in Dead Space and had the irritating tendency of collapsing on themselves without warning after only a few months. When the Iastret lost several ships to the sudden closing of the last Drain Vortex, leaving more than a hundred of their people stranded about six years from Iastret space with provisions to barely last a year, one would have assumed all interest in the wormholes would have faded. This would have been true for pretty much any other species, except the Iastret were crafted from a different cloth, and as though proving the utility of the wormholes would somehow avenge their lost people, they set out to dissect the data they had collected in earnest.

What they found was whereas the technology currently used for faster-than-light travel was able to skip a vessel along the surface of subspace, the Drain Vortexes acted as a whirlpool that created a passage of normal space through the surrounding subspace. They further concluded that with the right equipment and technical expertise the details of which made Boro’s mind slip through his own Drain Vortex to a secluded beach somewhere in the Mer Pacific, a ship could penetrate through the walls of the wormhole, and find itself fully immersed in subspace. From there, provided that everyone on board the ship survived the journey, which the Iastret whole-heartedly assured they would, the data that would be collected would be analyzed to allow the ship to puncture a hole back into normal space, and then freely back and forth, cutting down interstellar travel times down to fractions. To get this mission financed, the Iastret had essentially promised the whole galaxy – if there was anything of worth out there beyond Dead Space – a crossing that would theoretically take almost half a century would take less than a year. And similarly, a crossing of the entire Known Reaches would be a matter of a mere couple days and not six months. The Iastret were smart. This was a truth generally acknowledged, like the fact that the Thorians were arrogant bastards, and that the Hatvan were stuck-up bastards. But were the Iastret smart enough to break through the surface of subspace without crushing the ship to the size of a grain of sand? Boro wasn’t sure how keen he was to be a willing participant in that experiment. Not to mention that what remained unsaid during that briefing, despite hovering like a cold razor against the necks of the whole crew, was the main reason why the ship had to maximize its provisions at Yshot Station. This wormhole’s other end was flung out about a four years’ journey into Dead Space. If it were to collapse when they were on the other side, or worse, while they were still in it, best case scenario was being stranded several years’ journey from home without a single planet with even a shred of organic life along the way. --- Less than a week after the incident in the galley, just when Meslina started showing her face there again and even shared a laugh with Meeron as if nothing even happened but for the slight undertone that if something were to ever happen again, one of them might not live to laugh about it, Boro thought that he could make it to the end of the rotation without another pressure valve releasing all over his day. He was on bridge duty, a place that had frequently grown more crowded and where he was forced to appear more and more often. Yshot Station itself was in a far-flung corner of Iastret space near the frontier of the Thorian Empire, but the quickest way there lay through relatively dense confluence of Iastret and Vaparozh space, which required a bit more vigilance to stay off sensors. Increased vigilance, however, was pretty much where the excitement peaked and Boro spent most of the time on the bridge talking to Surch and trying not to gag whenever the Parsk Nahur moved and wafted some of his strong aroma in Boro’s direction. The little cautioning sound that came from Surch’s console nearly startled Boro into a call for red alert. “Report.” Boro ordered. “Report?” Surch chuckled. “I know you’ve got your infinite love for paperwork, but I don’t think I can squeeze an essay out of this one.” “Just tell me what’s going on.” “Rounding down? Absolutely nothing. Looks like there’s a small drop in power to engines, but nothing worth writing home about.” Surch had been using the phrase more and more frequently as they neared Yshot Station – the one time they would be given the opportunity to write home before going off the grid as they entered Thorian space. The way Surch joked, nothing ever happened on the ship that was worth writing home about and claimed that the only content of his communication back to Earth would be, “Hey ma, send samosas.” The alarm and the problem it identified were trivial, but trying to sneak a ghosted ship through a narrow strip between busy shipping lanes made Boro all the more aware that all trivial problems had ambitions to become something greater. Even if Surch, who was used to mostly flying single-person starfighters that required looking at issues with a narrow lens, was unphased by it, Boro liked to think there was a reason he had earned a command position well ahead of his classmate, and that was his ability to see the big picture. Unfortunately, what was supposed to be a reliable insight into the big picture was conspicuously quiet. Maggie Okoth, the Techever, was standing leaning with her back against the far curved wall of the bridge. She never sat, which for whatever reason bothered Boro. “Maggie, you have a read for me on that engine trouble?” Boro asked. Surch cleared his throat. “On that minor engine abnormality that Lieutenant Guraty guarantees won’t kill us in the long run.” “Nope,” the Techever answered, a baffling smile across her lips. “Nope?” “Pretty much a big ‘nope’.”

Sometimes my past writing decisions make me scratch my head and wonder why I insist on doing this to myself.

Alright, I get it, as The Bloodlet Sun was ramping up last summer before its release in September, I had to give it undue attention in order to fill up my buffer. I can respect that. I can also understand that because of this redistribution of time, I sidelined my goal of churning out two new revisions for my novel. I even, under different circumstances, would have understood not even finishing that first revision, especially since we then had a baby and it took me a while to get back into my writing routine. What I refuse to understand, as I finally pick up my Wake the Drowned again to see if I can take a crack at one more revision before going on the attempted publication journey, is abandoning that revision with three(!) pages left. Seriously, between the three pages left to edit on physical paper and a dozen pages left to input into my digital version, this is, at best, forty minutes of work. Forty minutes! When I had like five months in the year that I could have done it. So instead of putting a tidy ribbon on one revision, stewing on it for half a year, and coming back to it with a fresh approach, I have to deal with this scrawny little tail end of my work, shake it off and dive right back in. So naturally instead of just getting it over with, I’m letting the daunting task of my next revision weigh on me, scaring me away from finishing the last few pages, even though this particular task is so small and discreet. I know I come in here saying that writers shouldn’t see themselves as some special tortured souls for their writing. Yes, we share some common traits and there’s no shame in that but doubling down on it just seems exclusionary. And I know it sounds like this is what I’m doing right now, but it’s really just an example of my own neuroses translating to my writing work. I personally also find it ridiculous and a colossal waste of my time. I know in the end, I’ll tear this Band-Aid off at some point. Right now, I’m constructively procrastinating by pulling up a short story that I started writing a couple of years before the pandemic started but that touches on themes of quarantine and giving it some final edits using lessons learned from the actual quarantine we’ve all experienced. Not a waste of time by any means, but still not the thing I need to be working on to clear the logjam that’s been preventing me from putting the finishes touches on this novel and finally letting it rest. So I’ll just say this one was a lesson learned – procrastination now can only lead to worse procrastination later. Sounds like a tidy morale, but knowing how easily I get distracted from project to project, let’s see if this one has any chance of sticking.

I you hadn’t realized this by now, the best solution to having too many projects on the go and feeling that you’re barely keeping up with what you have on your plate is to put more onto your plate. This has obviously worked for me at buffets, the ensuing bellyache but an irrelevant detail, so surely it will work with my writing. Okay, yes, no rational part of my brain believes this. Unfortunately, the Venn diagram of the rational part of my brain and the writing part of my brain are two non-overlapping circles, so somebody please send help, I’ve done it again.

I don’t think I’ve mentioned this before but I’ve recently set out to find new audiences forThe Bloodlet Sun and joined Royal Road – one of the internet’s premier homes for web fiction. You can find the page here. It currently follows the same release schedule as my blog, but an account on Royal Road makes following stories easier if you prefer. Growing my story on Royal Road has been a slow process, which comes as no surprise so I’m not kicking myself over it. My installments tend to fall below average in length and frequency, and science fiction is not the genre that does best on the site. Still, I have five followers, which is success any way you cut it. Looking round Royal Road for the stuff that does do well, which is frequently hardcore progression-style LitRPGs, I had a brilliantly terrible idea – to try my hand at one of those stories myself. I’ve always enjoyed the fantasy genre, but outside of the story I’ve been telling to my kids over the last two years, haven’t made a serious attempt to write in it. This would be a great opportunity to flex those muscles, and on the off chance that I’m actually decent at it and the story attracts an audience, then I can use that platform to cross-promote The Bloodlet Sun and my other writing. Worst case scenario, the story is bad or falls flat with the website’s audience. It will get deleted and I will pretend it never happened. Either way, I would have had some crucial practice in and hopefully even get feedback out of it as a bonus. Time spent writing is never wasted. The other benefit of this particular project or experiment, however you want to label it, is I’ve had an idea for a fantasy story that I’ve been developing in my head for years now, unable to figure out what medium to commit it to. I’m sure other authors have that dusty shelf in their mind where ideas gather other ideas but mostly dust, never to see the light of day. So it felt good picking that up, plucking out the stray hairs and dust and whatever gunk collected on it, and then actually trying to polish into a full-fledged plot now that there’s some pressure of delivering a coherent product. Not sure if I ever would have tackled it without finding the web novel outlet for it, but I am certainly intent on giving it all I’ve got now that I’ve started. As of the time of this entry, I’m about 9,000 words, which translates to maybe 6-7 installments. However, we’re talking rough first draft here where most names are still placeholders and there’s a sea of red underlines and probably some unfinished sentences that I was totally going to complete later but “later” hasn’t arrived yet. If I had to guess, release is still three to four months away depending on how big of a chapter dump and buffer I want to start with. So it’s not exactly like it’s a slipshod hasty solution to getting more exposure for my other story. My whole writing career is a long game, and this is no exception – I’d rather take the time than put out some hot garbage out there. Speaking of things I’m putting out there, I just want to say that this decision isn’t easy. My writing will now span the entire gamut from a light(ish) fantasy story released on the internet to my continued attempts to get my novel-length contemporary fiction traditionally published. Whether fair or not, there’s a fear that delving into these genres and publication methods would hamper my ability to market myself in this other world I’m trying to break into. And maybe the fear is justified. At the same time, I’m not a fan of trying to cater myself to the tastes of others just because they might unfairly judge me. Life is too short to hide. So if you’re looking forward to a plucky orphan discovering the world, developing special powers and fighting great evil (stop me if you’ve heard this one before), then look forward to my own take on this, The Second Magus, coming some time this spring/summer.

“You have to pardon my crude metaphor,” Boro replied in response to the Intelligence officer’s assurances over the Thorian’s viability as an asset, “but if you tell me a lion’s got no teeth or claws and ask me to spend a night in its cage, it doesn’t mean I’ll be sleeping. Between Nabak, the Hatvan Troubles, and the Last Gasp, we’ll have people who either fought against them or knew somehow who did.” He could feel Meslina stiffen in the chair next to his. “There’s got to be a better way. If you can just go back to the previous screen.” The Intelligence officer obliged. “Admiral, you said we’re getting a full load of provisions at Yshot Station in any event. So why not just take the longer way around – would be far easier to snake down the border of Vaparozh territory, head a ways deep into Dead Space and then follow the borders of the Thorian Empire. And with barely any ships around, we can make better time without comprising our ghost.”

Admiral Fan stepped in then and the Intelligence officer once more took a step away and absorbed nearly her entire presence back into herself. Boro made a mental note to keep track of her, but moments later found himself neglecting to remember that she was around. “Your proposal, Commander Stevin, would still put you almost a month outside of your estimated arrival,” Admiral Fan explained. “A month that you likely don’t have.” “Better get there a month late, than not get there at all.” Boro hadn’t bothered to consider the possibility that his retort was out of line, but then Captain Pueson added his voice to the conservation. “We will get there, Commander Stevin. And we will get there on the timeline urged by our Iastret allies.” “If the Iastret want to get there that badly, then they should fly there themselves, they’ve got a much shorter trip, and the wings for it to boot.” “That’s quite enough, Commander.” Pueson’s voice dropped by a few degrees and Boro made sure to keep his eyes on Admiral Fan and off his Captain. “One of the founding principles of the Outer Rim Confederacy was to show that we could do better; that the rest of the Known Reaches had been missing out while Humans languished in their own little corner of space. This means showing that we have an ability to work with anyone out there, even with someone who had formerly been an enemy.” The Captain stood then, walking in measured steps to stand next to the Admiral. He may have initially chosen to sit with his people, but now he stood in front of them like a class of sullen schoolchildren – the message was clear as to who was in charge at the end of the day. “There are aspects of this mission that are uncomfortable, I’m not going to deny you that. But at all times you have to keep in mind that if we’re successful, we may be able to redraw the political map of the Known Reaches with the ORC, and by extension, Humanity, at its highest place. And once we’re there, I expect that we can show that military and technological superiority can be shared instead of hoarded, and it will start on this ship. Is that understood by everyone?” Captain Pueson’s expression was a mix of warmth and sternness that only made Boro queasy, but he nodded and agreed along with the other two, and the Captain seemed sufficiently pacified, though did not relinquish his new spot at the head of the room. If this sermon was any indication, this was gearing up to be a longer trip than Boro anticipated. To either side of him, some of the tension seemed to go out of Surch and Meslina’s spines, and they nodded. Boro always suspected this soft spot in Surch ever since their Academy days, one of the things that likely prevented him from rising as high as Boro had if they were in the same graduating class. Meslina though had initially struck him as someone who would have resisted this gradual erosion of the pride that Boro believed should have been the core tenet of Humanity’s continued foray into the Known Reaches. Boro, for his part, believed that it was no coincidence that the Human feet that included his father had been so instrumental at the Battle of Krevali and the Thorian’s defeat in the War of the Last Gasp shortly thereafter. Humanity, as other races would put it, even those who spent millennia under the boot of someone else’s empire, was late to the party. What these others had not considered, and what apparently more and more of the Navy high brass were losing their grasp on, was that the outsider’s perspective gave Humanity a fresh outlook, a clearer view into the stagnation that gripped the Known Reaches, where, save for the Last Gasp, the landscape had for years been defined by minor tussles. As a countermeasure to the Thorian Empire, came the ever-increasing idea of cooperation amongst all those who were not Thorian, which solidified the status quo, and therefore Humanity’s place on the periphery. “To your earlier point, Commander Stevin,” Admiral Fan continued with a light smile, “part of the Iastret research team that has been studying Drain Vortexes since their last appearance and that have been instrumental in identifying their potential will be joining you on board as well.” The Admiral then continued into a more detailed breakdown of what they were up against, complete with slide after slide of charts and graphs that made Boro think that if he hadn’t paid much attention to astrography during the Academy days it was decidedly too late to start now. And in any case, he had sufficient understanding to let the Iastret do their business without confounding him too much. |

Michael SerebriakovMichael is a husband, father of three, lawyer, writer, and looking for that first big leap into publishing. All opinions are author's own. StoriesUrsa Major Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed