Silver Wordsmith: An author's journey |

|

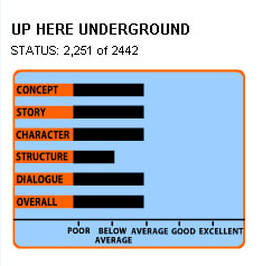

Today I want to introduce you to a novel project that has been very dear to me for quite some time. I’ve recently discussed my struggle with transitioning into my next novel, and blamed this on my addiction to outlines. A half-dozen ideas are all percolating still in my mind for varying lengths of time, but one project has now crossed the magic 10,000 word threshold for when I consider a novel to actually be in progress. And the two main reasons why this one seemed to pull ahead are that it’s my oldest unwritten projects that I’ve had and because, unlike the rest, it has a fully-fleshed out outline. Old dogs, am I right? The novel doesn’t yet have a working title, partly due to the fact that titles are a bit of a weak spot of mine (or one link in a chain mail armor of weakness). What it does have is a code title for the document, so for ease-of-reference let’s just use that until something more acceptable comes along than “Maple Vodka”. The reason why I refer to it as “Maple Vodka” will become clear soon enough, but first let me tell you a meandering background tale that I insist, at least to myself, will not bore you to death. As you’ve seen from my introduction to my first novel, Wake the Drowned, I brew ideas sometimes for years at a time before they ever see their first words committed to paper. Like Wake the Drowned, Maple Vodka has its roots from over a decade ago. I was still riding the high of having one of my short stories adapted into a short film, an adventure whose telling is best left for another day, and was trying to explore the lucrative screenwriting career I was obviously going to have. Back then, the regrettable Kevin Spacey’s production company, Trigger Street Productions, ran a peer-review site for amateur screenwriters. The premise was if you read and reviewed other people’s scripts, you could eventually post your own script and have it reviewed by complete industry noobs like yourself. For a year I eagerly worked to add my piece of garbage onto the communal landfill (to be perfectly honest, I did read a couple of scripts that were, in my opinion, worthy of Hollywood productions, but the overwhelming majority was similar to my own puerile attempt).  Well it wasn't last, so there's that Well it wasn't last, so there's that After having that script excoriated by the reviewing community, I decided to move onto my next project. This one would serve two purposes – my next script to be offered up to the Trigger Street masses, and also a way of outlining my next novel. As an outline, this was actually a decent idea because it allowed me to hash out my dialogue, which at the time was by far the weakest point of my writing. So I wrote up the first couple of scenes, made the most skeletal of outlines, and like every other large scale project I touched up until that point, off it went into the Land of the Forgotten, sort of. When I decided to take Wake the Drowned to an agent, I thought I would hedge my bets. After bits and pieces of my novel swam around in my head for about four years, on a long walk around the city I decided to hash out the same full outline that I did for Wake the Drowned. The idea was snuck into my email to the agent and because they never addressed it, instead choosing to opine on Wake the Drowned, nothing came of that outline, but it sat there for years on my hard drive whispering into my ear every so often. It's both a project that I’m excited to write, and one that terrifies me in its scope. I describe it simply enough – an alternative biography, a sort of personal alternate history. At least, that’s how it started. Imagine if, at the age of thirteen, I never moved to Canada. What kind of person would I have become? What parts of my personality and my future were shaped by my environment and what was inherent to me? Could I really be considered the same person? These are all the questions my protagonist, Paul, ponders during one of his identity crises, until one morning he wakes up, and finds out he never actually moved to Canada and has to deal with the person that he became in his native country. You see? Russian immigrant in Canada? Maple Vodka? As far as working titles go, I’ll say this one isn’t half bad. In the decade since I first thought of this idea, there have been significant changes, both to myself and my story. Firstly, even though it was going to be a literal exploration of what I would have been like if I had not moved, Paul had slowly diverged from me in terms of personal experiences and personality. Sure, he still shares a lot of my childhood experience and certain traits, but changes needed to be made to provide at least some objective separation, and artistic liberty was required.  I don't know what I would do without Google Street View. This is what greets Paul on his first morning back in Moscow I don't know what I would do without Google Street View. This is what greets Paul on his first morning back in Moscow The novels relationship to the origin/destination dichotomy had also shifted. The novel was conceptualized to show a very obtuse picture of Canada being good and Russia being bad. But the country I had not visited in almost twenty years has changed in unprecedented ways. At least in Moscow, beautification projects have changed the face of the city, modern apartment blocks repaved outdoor farmers’ markets, pedestrian crossings have transformed the streets. But at the same time, whatever hope remained in the 90s seemed to have been sapped. The country has reshaped itself as a pariah, as one against the world, steering the people against external enemies instead of the internal ones sitting at the top of the food chain. Not only that, but I myself have developed a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between person and place. We are a product of our own free will as much as we are about where we are from. The novel has thus become more introspective to the main character. So as I’m starting to work my way through the first quarter of the novel, all these things are rearing up and threatening to scare me away into safer waters, you know, the ones where I’m bouncing from idea to idea unable to commit. I’ve embraced the challenge of writing about a country I personally haven’t been to for more than half my life, but one that has given me an inexorable part of the soul that longs to write. I’ve got a few windows into Russia I can still use, so I’m not flying completely blind. I also know that this can’t be a long-winded essay about my own opinions. Paul needs to be real to me, he needs to be thrown in this situation and genuinely try to find his way out of it, to genuinely react to the face that he sees in the mirror. So there it is, what is likely to become my second novel if things go well. Meanwhile, I should write some outlines, otherwise I’ll have nothing to do once this one is done.

1 Comment

I have recently put the finishing touches on the third draft of my first novel, Wake the Drowned. It’s been a process that has lasted almost two years, so I hope that not only did I improve the manuscript, but actually managed to learn something along the way. So without further introduction, here is an arbitrary number of writing tips I have distilled out of the editing process for draft 3.

Tip 1: Just let it spill out Self-editing as you go is probably one of the worst sins a writer can commit against themselves. I still find myself, during what should be a breezy first draft, questioning “is this scene dragging on too long?” or “wouldn’t this be better in another part of the book?” or “does this aside actually serve any purpose?” These are all extremely valid questions and answering them will go a long way to improving your work. However, they shouldn’t be asked at the writing stage and are best left for the editing stage. I spent years writing the first draft of the novel. And then another year editing it into the second draft. You’d think with all the self-editing I did along the way, everything would have come together by then. Wrong. So much of draft 3 did not just involve editing for phrasing or brevity. I was moving around chapters, adding new chapters, merging chapters from different parts of the book into each other. All that time that I spent overthinking as I wrote was largely wasted, because difficult decisions are being made right now. So when you’re writing that first draft, just write. Put down every scene you think of writing onto the page. At least now it’s there, saved, and ready to be dealt with later. Then, when you’re editing, apply a liberal does of the following tip, and then you’ve done yourself and your work a great favour. Tip 2: Be merciless My first draft clocked in at about 95,000 words, and after the first set of revisions, the second draft came it at around 73,000 – that’s almost a quarter of the original manuscript gone, so I thought I was in a good spot. The third draft of the novel included additional chapters and material that amounted to approximately ten thousand words, yet the length of the manuscript remained unchanged. That means through this edit, another 10,000 words came off the books. Now a full third of the original was gone. Granted, this process was gradual and didn’t feel so drastic, but think about what this means. Imagine writing 32,000 words and then just … deleting them. Not everything you write will be gold, and part of editing is panning for that gold so that the end product is a distillation of your writing. Imagine yourself as an athlete with the ability to take away some of your failed attempts. Imagine the career you could have. This is presented to you as an option in writing, so it would be a crime against yourself to not seize the opportunity. Cut. And don’t let the writer you used to be dictate what your writing should look like. Tip 3: There no such thing as too slow Slow and steady wins the race. It’s not a sprint, it’s a marathon. On the surface, all platitudes to make yourself feel better about procrastination, but I found them to be strangely true. Yes, looking back at the fact that I finished writing the first draft in 2015 and it’s been more than three years later and I’ve only made it through two major revision cycles may sound a wee bit discouraging, but what’s the rush? I’ve got a day job, a family, *gasp* other hobbies. I can’t afford to throw myself in, to marry myself to the “writer’s lifestyle” whatever that might mean to you. So why should I be hard on myself for taking my time? I’m in my early thirties. I’m still learning life, still reading, still improving my writing. They still make “Top 40 Writers Under 40” lists so I’ve got a lot of room here. No one wins a lifetime achievement awards for a decade worth of work. No one writes an autobiography before they’re twenty. Okay, that last one may not be true, but you get the point. Tip 4: You are not an ostrich It’s easy to breeze through an edit, correcting typos, changing wording, maybe even tweaking dialogue to make it more natural. But then you get to a page, or maybe a whole scene, and something just doesn’t feel right. Maybe it’s the pacing, or maybe it doesn’t serve the plot, or maybe the tone is wrong or the characterization is inconsistent. Maybe it’s just a feeling that something is amiss. Do you a) wrack your brains about how to fix the problem, or b) do you stick your head in thee send and pretend you didn’t see anything. I’ve certainly done the latter with some of my previous edits and have paid for it in this draft. I’ve already got my eye on the next draft and have a feeling I know what I need to tackle. For years I’ve ignored an uncomfortable feeling about a certain aspect or my story. But now that we’re squarely in 2018, I find myself needing to make some significant edits to avoid what I find to be cultural appropriation. I won’t be happy until all those wrinkles are ironed out. So why dodge it? If something doesn’t feel right, try to figure out why, and how to fix it. Tip 5: You didn’t marry your outline I’ve already lamented about how I seem to be unable to start a project without a robust outline in place. While this so far appears to be a prerequisite for me to actually get writing, the outline is just a skeleton of the work. But bones break, get re-set, limbs are amputated, okay, maybe the choice of metaphor was a mistake, but in any case, what you thought your story would look like before you even started writing it should not dictate how your story should develop. I’ve already gone at length about at the transformations Wake the Drowned has taken over the years, and it only really took off once an outline was in place. So I owe that much to it. But I recently found one of my early outlines for it and almost laughed at how much it has changed. For this particular draft, I found significant “dead zones” in the plot, or as I like to call them “doldrums” where there’s neither moving action nor character developed (I’ll go into more detail about my plot graphs some other time). I worked hard to whittle these down and yet the problem was right there from the beginning – so much of my outline was basically “and then Charlie walks around for a while and basically does fuck all”. How I thought that would make for engaging story, I’ll never know. So once the first draft is complete, the outline has served its purpose. Your story is now an organic entity in your hands and you need to help its development. If that means throwing your original plot twists into the dumpster, that’s fine. Save them onto a file somewhere on your computer so you can maybe go back and be inspired by them later. So that’s about all the drops of wisdom I have to share – felt like juicing a turnip with your bare hands. Hopefully this will make the road through draft 4 a less painful affair. I’m in an introspective mood, which spells trouble for both brevity and comprehension, but in any case, I will try to keep this focused. I’ve recently returned from a conference in Toronto, my first visit to the city since my wife and I moved away seven years ago. In Canada, Vancouver has always been home, but we did spend an amazing three years in our largest city while I attended law school at the University of Toronto. So T-Dot, the Big Smoke, Hogtown, or whatever outlandish nickname you want to give it (Centre-of-the-universe, as those outside Toronto are apt to call it), is a second home. I’m no stranger to having second or third homes. I was born in Budapest and spent many summers there, and I grew up in Moscow, so I’m used to leaving behind places that have been dear to me. But this is the first time I’ve come back to a place after such a long time. Everything changes. Whether people or places, change is woven into the fabric of existence. To expect something to preserve itself exactly as you remember it is to deny that someone or someplace a core part of their nature. Even our Vancouver neighbourhood that we moved into after Toronto has undergone a lot of changes since that time. Stores that had been opened for decades had closed, some being replaced by cannabis dispensaries. A grocery store had a condo tower built on top of it. This all happens so gradually that like the proverbial boiling frog, even though you’re kind of aware of the temperature becoming uncomfortable, the change is just too gradual to truly appreciate.  Then you get dropped into Toronto after a seven-year absence, a city that is known for having two seasons – winter and construction, and pick a random intersection in Downtown and scan your surroundings. The skyline is dotted with cranes erecting ever-higher towers, constantly increasing residence stock without ever alleviating the cost of housing. This never ends, once a building is finished, another one pops up somewhere. So it’s a neat feeling coming across a beautiful light-blue skyscraper, and scratching your head trying to figure out what was there before. But if you can’t remember, it no longer matters, it’s left your life, leaving no impact whatsoever except this vague uneasy feeling that change tends to elicit. Then there’s the stuff you do remember being there. Our local neighborhood No Frills store (probably one of the most “no frills”, as the name implies, grocery stores in Canada) was replaced by a much shinier looking FreshCo. And the old menacing 1960s apartment block that rose above it is now another glass condo tower reaching above its neighbours. This little visual gentrification of St. James Town was a bit of a shock in a city that, as I already mentioned, suffers from an ongoing housing crisis. In the eternal struggle between old and new, I also came across a stark example of a Toronto building strategy – incorporating an old façade into a new building. Heck, there’s a building not too far from the Hockey Hall of Fame that is entirely within what is essentially an indoor mall. So here it is, a clock tower of some unknown historical significance that was chosen to withstand the unstoppable march of progress. Our own apartment building was still there. That was welcome news. The window of our first floor corner apartment, where we spent three years sharing 350 square feet was covered by a clothesline of old towels and sheets. Beyond that impenetrable façade, because how creepy would it be to ask for a tour of the old place, was the first real home we made. Now it’s only accessible through photos and memories, but it’s still there, with the familiar cracks and imperfections we made our own. Which is more than I can say for my second home in Toronto – the law school. Despite getting a whole new building clamped onto its side, from a certain angle, the two law school buildings don’t look any different. The iconic façade we put on all our hoodies and T-shirts is still there – the view at the end of my morning walks. And when you first walk inside, it still hits you with that smell – the history that has seeped into the walls of so many repurposed Toronto buildings.  But then when you exist the foyer, you’re in a whole different world. Sure, Bora Laskin’s bust still sits on its pedestal next to the library’s entrance, but the entrance has moved. The copy stations where I’d print out freshly warm essays to hand in is nowhere to be found. The study nooks on the second floor where I’d eat baby carrots and watch episodes of One Piece are no longer there. I tried to track down any of my old classrooms, but had no luck. Either the new layout has completely messed with my sense of direction or it’s all gone. Photos of graduating classes where you’d be able to pick out half the notable judges and federal Liberal politicians of the last half-century have all been hidden away. My law school, the entity that has awarded me my degree, is still there, but the law school that I truly knew is gone. I would never be able to tell my kids that here is where their mom leaned against that stone pillar while she waited for me and got bronchitis in our first week there. Such a tiny little thing, a silly insignificant story that no longer has the aid of having a live location. Like with the apartment, the memory is there, but the physical space is gone. It shouldn’t really be a big deal but it is. In my early thirties it’s finally creeping up on me. The country I spent the first years of my life is gone. The political ideology that raised my parents is almost extinct. Yet this, a remodeling of a law school is what gets to me. It brings to the forefront the power of memories. People, places, and things all go, but they all live a second life in our memories. We are faced with a flood of photographic evidence. Something our grandparents and even our parents didn’t have. It’s so easy to whip out the phone and observe, but it’s a very different feeling from experience. Now, I’m now trying to turn this into a “technology is bad” kind of luddite rant, but I can’t stress enough the need to appreciate the moment. To truly sink into the people and the places we hold dear to us. I know I’m getting philosophical over some pretty basic stuff, but there’s one thing to know something, and there’s another to truly feel it; deep down in your bones kind of feel it. And this, I feel, is something that is one of the goals of my writing: to turn that inward feeling outward. At the end of the day, I want to leave readers with a memory of the story. |

Michael SerebriakovMichael is a husband, father of three, lawyer, writer, and looking for that first big leap into publishing. All opinions are author's own. StoriesUrsa Major Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed